Table of Contents

Coatlicue was an Aztec goddess who played a critical role in Aztec mythology. She is the mother of the moon, stars, and the sun, and her myths are tied closely to those of her last born, Huitzilopochtli the sun god, who protects her from his angry siblings.

Known as a fertility goddess, as well as a deity of creation, destruction, birth, and motherhood, Coatlicue is known for her intimidating depiction and skirt of snakes.

Who is Coatlicue?

A goddess of the earth, fertility, and birth, Coatlicue’s name literally translates as “snakes in her skirt”. If we look at her depictions in ancient Aztec statues and temple murals, we can see where this epithet came from.

The goddess’ skirt is intertwined with snakes and even her face is made out of two snake heads, facing each other, forming a giant snake-like visage. Coatlicue also has big and flabby breasts, indicating that, as a mother, she has nurtured many. She also has claws instead of fingernails and toes, and she wears a necklace made out of people’s hands, hearts, and a skull.

Why Does a Fertility and Matriarch Deity Look So Terrifying?

Coatlicue’s image is unlike anything else we see from other fertility and motherly goddesses across the world’s pantheons. Compare her with deities such as the Greek goddess Aphrodite or the Celtic Earth Mother Danu, who are depicted as beautiful and human-like.

However, Coatlicue’s appearance makes perfect sense in the context of the Aztec religion. There, like the goddess herself, snakes are symbols of fertility because of how easily they multiply. Additionally, the Aztecs used the image of snakes as a metaphor for blood, which also related to the myth of Coatlicue’s death, which we’ll cover below.

Coatlicue’s claws and her ominous necklace are related to the duality the Aztecs perceived behind this deity. According to their worldview, life and death are both a part of an endless cycle of rebirth.

Every so often, according to them, the world ends, everyone dies, and a new Earth is created with humanity springing forth once again from their ancestors’ ashes. From that point of view, perceiving your fertility goddess like a mistress of death is quite understandable.

Symbols and Symbolism of Coatlicue

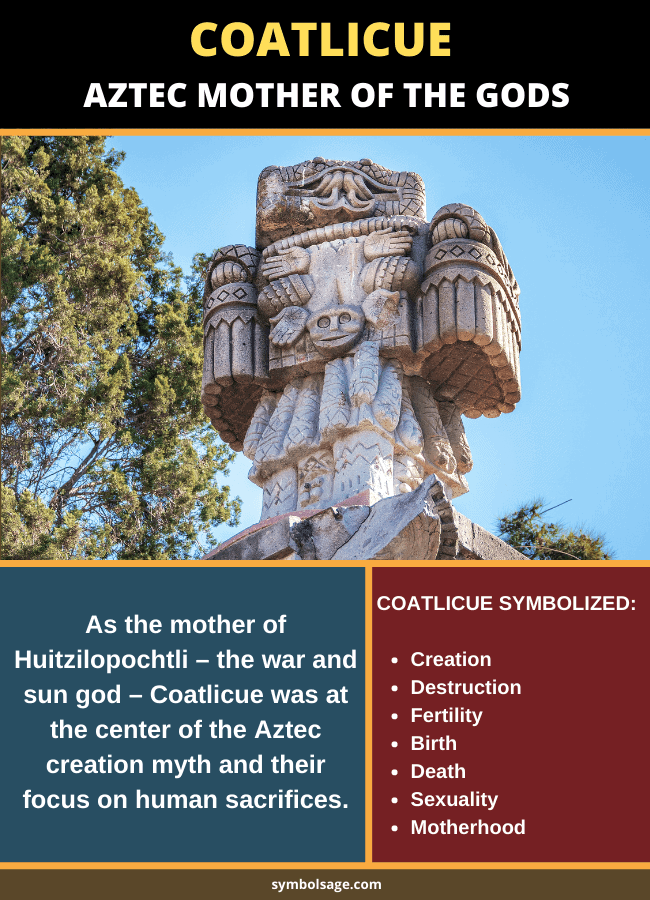

Coatlicue’s symbolism tells us much about the Aztecs’ religion and worldview. She represents the duality they perceived in the world: life and death are the same, birth requires sacrifice and pain, humanity is built on the bones of its ancestors. That’s why Coatlicue was worshipped as a goddess of both creation and destruction, as well as of sexuality, fertility, birth, and motherhood.

The association of snakes with both fertility and blood is also unique for the Aztec culture. There’s a reason why so many Aztec gods and heroes had the word snake or Coat in their names. The snakes’ use as a metaphor (or a sort of visual censoring) for spilling blood is also unique and informs us of the fates of many Aztec gods and characters we only know from murals and statues.

Mother of the Gods

The Aztec pantheon is quite complicated. That’s largely because their religion is made of deities from different religions and cultures. For starters, the Aztec people took some ancient Nahuatl deities with them when they migrated south from Northern Mexico. Once they arrived in Central America, however, they also incorporated much of the religion and culture of their newfound neighbors (most notably, the Mayans).

Additionally, the Aztec religion went through some changes during the brief two-century life of the Aztec Empire. Add the Spanish invasion’s destruction of countless historic artifacts and texts, and it’s hard to discern the exact relationships of all the Aztec deities.

All this to say that while Coatlicue is worshipped as the Earth Mother, not all gods are always mentioned as related to her. Those deities that we know come from her, however, are quite central to the Aztec religion.

According to Coatlicue’s myth, she is the mother of the moon as well as of all the stars in the sky. The moon, Coatlicue’s one daughter, was called Coyolxauhqui (Bells Her Cheeks). Her sons, on the other hand, were numerous and were called Centzon Huitznáua (Four Hundred Southerners). They were the stars in the night’s sky.

For a long time, the Earth, moon, and stars lived in peace. One day, however, as Coatlicue was sweeping the top of mount Coatepec (Snake Mountain), a ball of bird feathers fell on her apron. This simple act had the miraculous effect of leading to the immaculate conception of Coatlicue’s last son – the warrior god of the sun, Huitzilopochtli.

The Violent Birth of Huitzilopochtli and Coatlicue’s Death

According to the legend, once Coyolxauhqui learned that her mother was pregnant again, she became enraged. She summoned her brothers from the sky, and together they all attacked Coatlicue, in an attempt to kill her. Their reasoning was simple – Coatlicue had dishonored them by having another child without warning.

Huitzilopochtli is Born

However, when Huitzilopochtli, still in his mother’s belly, sensed his siblings’ attack, he immediately jumped out of Coatlicue’s womb and to her defense. Not only did Huitzilopochtli effectively birth himself prematurely, but, according to some myths, he was also fully armored as he did so.

According to other sources, one of Huitzilopochtli’s four hundred star brothers – Cuahuitlicac – defected and came to the still-pregnant Coatlicue to warn her of the attack. It was that warning that spurred Huitzilopochtli to be born. Once out of his mother’s womb, the sun god put on his armor, picked up his shield of eagle feathers, took his darts and his blue dart-thrower, and painted his face for war with a color called “child’s paint”.

Huitzilopochtli Defeats His Siblings

Once the battle atop Mount Coatepec started, Huitzilopochtli killed his sister Coyolxauhqui, cut off her head, and rolled her down the mountain. It’s her head that’s now the moon in the sky.

Huitzilopochtli was also successful in defeating the rest of his brothers, but not before they had killed and decapitated Coatlicue. This is likely the reason why Coatlicue is not only depicted with snakes in her skirt – the blood of childbirth- but also with snakes coming out of her neck instead of a human head – the blood coming out after she was decapitated.

So, according to this version of the myth, the Earth/Coatlicue is death, and the Sun/Huitzilopochtli guards her corpse against the stars while we inhabit it.

The Reinvention of The Coatlicue and Huitzilopochtli Myth

Interestingly, this myth is at the center of not just the Aztecs’ religion and worldview but most of their lifestyle, government, war, and more. Simply put, Huitzilopochtli and Coatlicue’s myth is why the Aztecs were so dead set on ritual human sacrifices.

At the center of it all seems to be the Aztec priest Tlacaelel I, who lived during the 15th century and died some 33 years before the Spanish invasion. Priest Tlacaelel I was the son, nephew, and brother of several Aztec emperors too, including his famous brother Emperor Moctezuma I.

Tlacaelel is most notable for his own achievement – that of reinventing the Coatlicue and Huitzilopochtli myth. In Tlacaelel’s new version of the myth, the story unfolds in largely the same manner. However, after Huitzilopochtli succeeds in driving his siblings away, he has to keep fighting them to keep his mother’s body safe.

So, according to the Aztecs, the moon and stars are in a constant battle with the sun over what’s going to happen to the Earth and all the people on it. Tlacaelel I postulated that the Aztec people were expected to perform as many ritual human sacrifices as possible in Huitzilopochtli’s temple in the capital city Tenochtitlan. This way, the Aztecs could give the sun god more strength and help him fight off the moon and the stars.

This is why the Aztecs focused on the heart of their victims too – as the most vital source of human strength. Because the Aztecs had based their calendar on that of the Maya, they had noticed that the calendar formed 52-year cycles or “centuries”.

Tlacaelel’s dogma further speculated that Huitzilopochtli has to fight his siblings at the end of every 52-year cycle, necessitating even more human sacrifices on those dates. If Huitzilopochtli were to lose, the whole world would be destroyed. In fact, the Aztecs believed that this had already happened four times before and they were inhabiting the fifth incarnation of Coatlicue and the world.

Coatlicue’s Other Names

The Earth Mother is also known as Teteoinnan (Mother of the Gods) and Toci (Our Grandmother). Some other goddesses are also often associated with Coatlicue and might be related to her or may even be alter-egos of the goddess.

Some of the most famous examples include:

- Cihuacóatl (Snake Woman) – the powerful goddess of childbirth

- Tonantzin (Our Mother)

- Tlazoltéotl – the goddess of sexual deviancy and gambling

It’s speculated that all these are different sides of Coatlicue or different stages of her development/life. It’s worth remembering here that the Aztec religion was probably somewhat fragmented – various Aztec tribes worshipped different gods at various periods of time.

After all, the Aztec or Mexica people weren’t just one tribe – they were made up of many different peoples, especially in the latter stages of the Aztec Empire when it covered giant parts of Central America.

So, as often happens in ancient cultures and religions, it’s quite likely that old deities such as Coatlicue had gone through multiple interpretations and stages of worship. It’s also likely that various goddesses from different tribes, religions, and/or ages all became Coatlicue at one point or another.

In Conclusion

Coatlicue is one of the many Aztec deities we know only fragments about. However, what we do know of her shows us clearly how crucial she was for the Aztec religion and lifestyle. As the mother of Huitzilopochtli – the Aztecs’ war and sun god – Coatlicue was at the center of the Aztec creation myth and their focus on human sacrifices.

Even before Tlacaelel I’s religious reform elevated Huitzilopochtli and Coatlicue to new heights of worship during the 15th century, Coatlicue was still worshipped as the Earth Mother and a patron of fertility and births.