Table of Contents

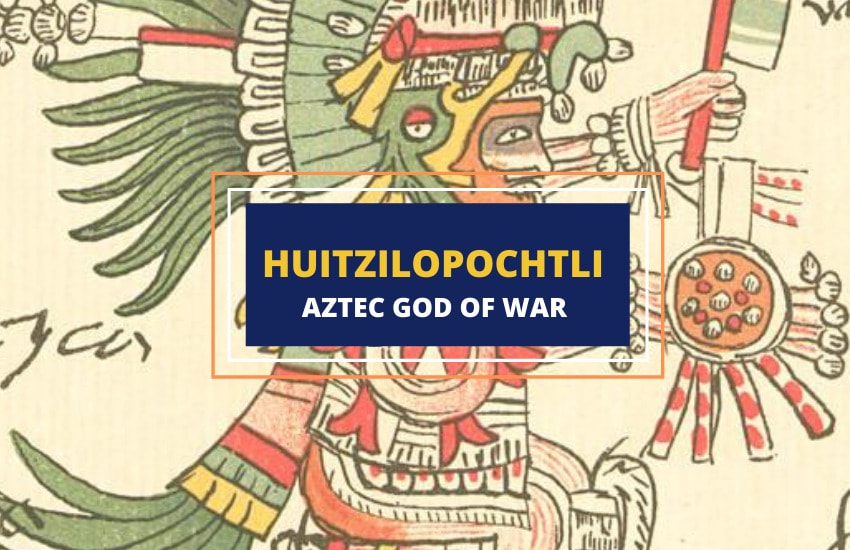

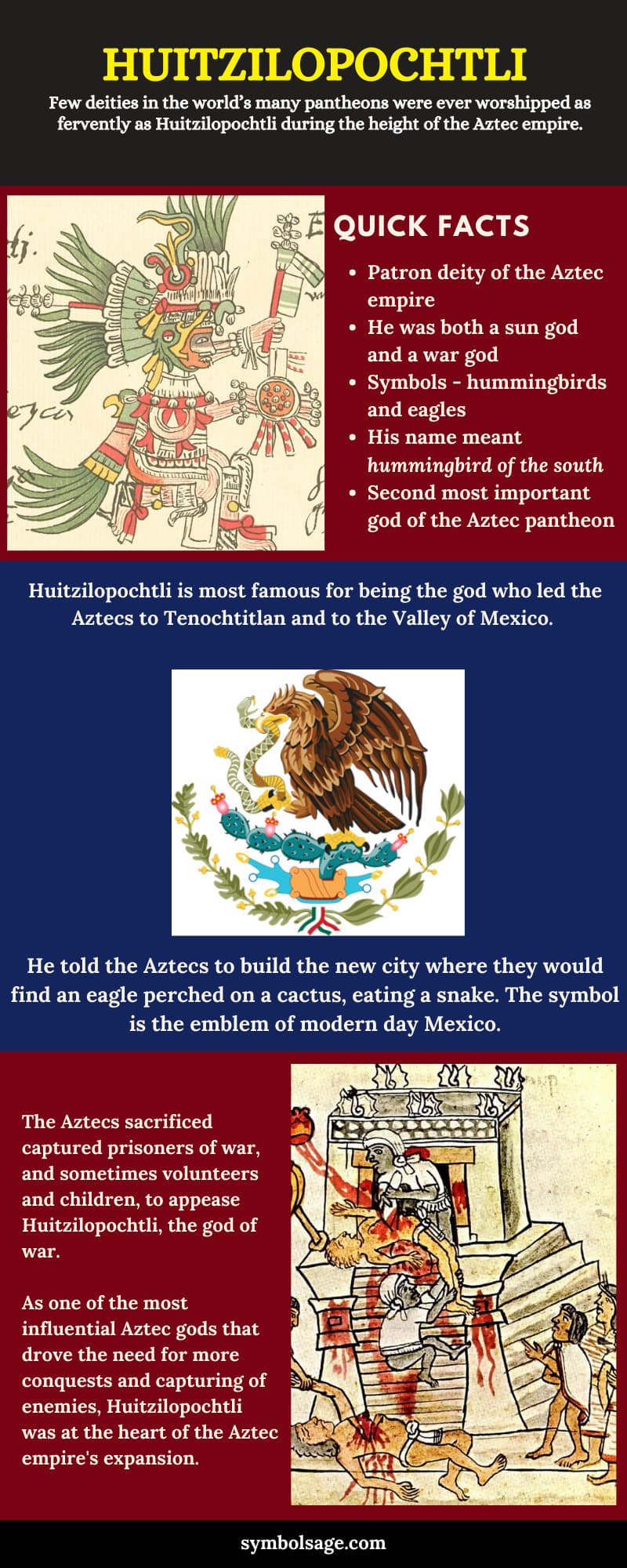

For most of Aztec history, Huitzilopochtli was worshipped as the patron deity of the Aztec empire. In his name the Aztecs built gigantic temples, performed countless thousands of human sacrifices, and conquered huge parts of Central America. Few deities in the world’s many pantheons were ever worshipped as fervently as Huitzilopochtli during the height of the Aztec empire.

Who is Huitzilopochtli?

Both a sun god and a war god, Huitzilopochtli was the main deity in most of the Nahuatl-speaking Aztec tribes. As these tribes varied quite a bit between each other, there were different myths told about Huitzilopochtli among them.

He was always a sun god and a war god, as well as a god of human sacrifices, but his significance differed depending on the myth and the interpretation.

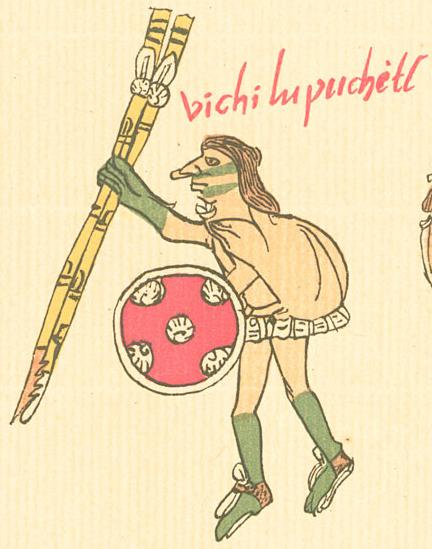

Huitzilopochtli also came with different names depending on the tribe and their native language. An alternative spelling in Nahuatl was Uitzilopochtli while some other tribes also called the god Xiuhpilli (Turquoise Prince) and Totec (Our Lord).

As for the meaning of his original name, in Nahuatl, Huitzilopochtli is translated as Hummingbird (Huitzilin) Of the Left or Of The South (Opochtli). That’s because the Aztec viewed the south as the “left” direction of the world and the north as the “right” direction. An alternative interpretation would be Resurrected Warrior of the South as the Aztecs believed hummingbirds were the souls of dead warriors.

Etymology aside, Huitzilopochtli is most famous for being worshipped as the god who led the Aztecs to Tenochtitlan and to the Valley of Mexico. Before that, they lived in the plains of northern Mexico as several disjointed hunter and gatherer tribes. However, all that changed when Huitzilopochtli led the tribes south.

The Founding of Tenochtitlan

There are several legends of the Aztecs’ migration and the founding of their capital but the most famous one comes from the Aubin Codex – the 81-page history of the Aztecs written in Nahuatl after the Spanish conquest.

According to the codex, the land in northern Mexico the Aztecs used to live in was called Aztlan. There, they lived under a ruling elite called Azteca Chicomoztoca. However, one day Huitzilopochtli ordered the several main Aztec tribes (Acolhua, Chichimecs, Mexica, and Tepanecs) to leave Aztlan and to travel south.

Huitzilopochtli also told the tribes to never call themselves Aztec again – instead, they were to be called Mexica. Nevertheless, the different tribes kept most of their former names and history remembers them with the general term Aztecs. At the same time, modern-day Mexico did take the name given to them by Huitzilopochtli.

As the Aztec tribes traveled south, some legends say that Huitzilopochtli guided them in his human form. According to other stories, Huitzilopochtli’s priests carried feathers and images of hummingbirds on their shoulders – the symbols of Huitzilopochtli. It’s also said that, at night, hummingbirds told the priests where they should travel toward in the morning.

At one point, Huitzilopochtli is said to have left the Aztecs in the hands of his sister, Malinalxochitl, who supposedly founded Malinalco. However, the people hated Huitzilopochtli’s sister so he put her to sleep and ordered the Aztecs to leave Malinalco and travel further south.

When Malinalxochitl woke up she grew angry at Huitzilopochtli, so she gave birth to a son, Copil, and ordered him to kill Huitzilopochtli. When he grew up, Copil confronted Huitzilopochtli and the sun god slew his nephew. He then carved Copil’s heart out and threw it in the middle of Lake Texcoco.

Huitzilopochtli later ordered the Aztecs to search for Copil’s heart in the middle of the lake and build a city over it. He told them that the place would be marked by an eagle perched on a cactus and eating a snake. The Aztecs found the omen on an island in the middle of the lake and established Tenochtitlan there. To this day, the eagle perched on a cactus with a snake in its claws is the national emblem of Mexico.

Huitzilopochtli and Quetzalcoatl

According to one of the several origin stories of Huitzilopochtli, he and his brother Quetzalcoatl (The Feathered Serpent) created the Earth, Sun, and humanity as a whole. Huitzilopochtli and Quetzalcoatl were brothers and sons of the Creator couple of the Ōmeteōtl (Tōnacātēcuhtli and Tōnacācihuātl). The couple had two other children – Xīpe Tōtec (Our Lord Flayed), and Tezcatlipōca (Smoking Mirror).

However, after creating the Universe, the two parents instructed Huitzilopochtli and Quetzalcoatl to bring order to it. The two brothers did so by creating the Earth, the Sun, as well as people and fire.

Defender of the Earth

Another – arguably more popular – creation myth tells of the Earth goddess Coatlicue and how she was impregnated in her sleep by a ball of hummingbird feathers (the soul of a warrior) on Mount Coatepec. However, Coatlicue already had other children – she was mother to the moon goddess Coyolxauhqui as well as the (male) Stars of the Southern Sky Centzon Huitznáua (Four Hundred Southerners), a.k.a. Huitzilopochtli’s brothers.

When Coatlicue’s other children found out that she was pregnant, they grew angry and decided to kill her as she was pregnant with Huitzilopochtli. Realizing that, Huitzilopochtli birthed himself out of his mother in full armor (or immediately armored up, according to other versions) and attacked his siblings.

Huitzilopochtli beheaded his sister and threw her body from Mount Coatepec. He then chased his brothers away as they fled across the open night sky.

Huitzilopochtli, Supreme Leader Tlacaelel I, and Human Sacrifices

From that day on, the sun god Huitzilopochtli is said to constantly be chasing the moon and stars away from their mother, the Earth. That’s why all celestial bodies (seem to) rotate the Earth, according to the Aztecs. This is also why the people believed it’s important to provide nourishment to Huitzilopochtli via human sacrifices – so that he is strong enough to keep chasing his siblings away from their mother.

If Huitzilopochtli is to grow weak due to lack of sustenance, the moon and the stars will overpower him and destroy the Earth. In fact, the Aztecs believed that this has already happened in previous versions of the universe, so they were adamant that they wouldn’t let Huitzilopochtli go on without nourishment. By “feeding” Huitzilopochtli with human sacrifices, they believed that they were postponing the destruction of the Earth by 52 years – a “century” in the Aztec calendar.

The whole concept of this need for human sacrifices seems to have been put into place by Tlacaelel I – the son of the son of Emperor Huitzilopochtli and the nephew of Emperor Itzcoatl. Tlacaelel was never an emperor himself but he was a cihuacoatl or a supreme leader and advisor. He is largely credited as the “architect” behind the Triple Alliance that was the Aztec Empire.

However, Tlacaelel was also the one who elevated Huitzilopochtli from a smaller tribal god into the god of Tenochtitlan and of the Aztec Empire. Before Tlacaelel, the Aztecs actually worshipped other gods much more vehemently than they did Huitzilopochtli. Such gods included Quetzalcoatl, Tezcatlipoca, Tlaloc, the former sun god Nanahuatzin, and others.

In other words, all the above mythos about Huitzilopochtli creating the Aztec people and leading them to Tenochtitlan were established after the fact. The god and large parts of its mythology existed before Tlacaelel but it was the cihuacoatl who elevated Huitzilopochtli into the main deity of the Aztec people.

Patron God of Fallen Warriors and Women in Labor

As is written in the Florentine Codex – a collection of documents on the religious cosmology, ritual practices, and culture of the Aztecs – Tlacaelel I had a vision that the warriors who died in battle and women who died in childbirth would serve Huitzilopochtli in the afterlife.

This concept is similar to war/main gods in other mythologies such as Odin and Freyja in Norse mythology. The unique twist of mothers dying in childbirth also been counted as warriors who’ve fallen in battle is much rarer, however. Tlacaelel doesn’t name a specific place where these souls would go; he just says that they join Huitzilopochtli in his palace south/to the left.

Wherever this palace is, the Florentine Codes describes it as shining so bright that the fallen warriors have to raise their shields to cover their eyes. They could only see Huitzilopochtli through the holes in their shields, therefore only the bravest warriors with the most damaged shields would manage to properly see Huitzilopochtli. Then, both the fallen warriors and the women who died at childbirth were transformed into hummingbirds.

The Templo Mayor

Templo Mayor – or The Great Temple – is the most famous structure in Tenochtitlan. It was devoted to the two most important gods for the Mexica people in Tenochtitlan – the rain god Tlaloc and the sun and war god Huitzilopochtli.

The two gods were considered “of equal power” according to Dominican Friar Diego Durán and were certainly equally important for the people. The rainfall determined the people’s crop yields and way of life, while war was a never-ending part of the expansion of the empire.

The temple is believed to have been expanded eleven times during the existence of Tenochtitlan with the last major expansion happening in 1,487 AD, just 34 years before the invasion of the Spanish conquistadors. This last upgrade was also celebrated with 20,000 ritual sacrifices of prisoners of war captured from other tribes.

The temple itself had a pyramidal shape with two temples sitting at its very top – one for each deity. Tlaloc’s temple was on the northern part and was painted with blue stripes for rainfall. Huitzilopochtli’s temple was to the south and was painted red to symbolize the blood spilled in war.

Nanahuatzin – The First Aztec Sun God

When speaking about Aztec sun gods, we have to spare a mention for Nanahuatzin – the original solar god from the old Nahua legends of the Aztecs. He was known as the humblest of the gods. According to his legend, he sacrificed himself in fire to make sure that he would continue to shine over the Earth as its sun.

His name translates as Full of Sores and the suffix –tzin implies familiarity and respect. He is often depicted as a man emerging from a raging fire and he’s thought to be an aspect of the Aztec deity of fire and thunder Xolotl. This can depend on the legend, however, as do some other aspects of Nanahuatzin and his family.

Either way, the reason most people think of Huitzilopochtli when talking about the “Aztec sun god” is that the latter was eventually declared as such over Nanahuatzin. For better or for worse, the Aztec empire simply needed a more war-like and aggressive patron god than the humble Nanahuatzin.

Symbols and Symbolism of Huitzilopochtli

Huitzilopochtli is not just one of the most famous Aztec gods (possibly second only to Quetzalcoatl who is very well-known today) but he was also arguably the most influential one. The Aztec empire was built on a never-ending conquest and war over the other tribes in Mesoamerica and the worship of Huitzilopochtli was at the very heart of that.

The system of sacrificing enemy captives to Huitzilopochtli and allowing the conquered tribes to self-govern as client states in the empire had proved very effective up until the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors. Ultimately, it backfired on the Aztecs as many of the client states and even members of the Triple Alliance betrayed Tenochtitlan to the Spanish. However, the Aztecs couldn’t have foreseen the sudden arrival from the east.

Barring that untimely end of the Aztec empire, the worship of Huitzilopochtli was definitely the driving force behind the Aztec empire. The mythos surrounding the possible end of the world if Huitzilopochtli isn’t “fed” captured enemy warriors could have very likely inspired more conquest from the Aztecs across Mesoamerica over the years.

Symbolized by hummingbirds and eagles alike, Huitzilopochtli lives on to this day, as the emblem of modern-day Mexico still refers to the establishment of the city of Tenochtitlan.

Importance of Huitzilopochtli in Modern Culture

Unlike Quetzalcoatl who is represented or referenced in countless modern books, movies, animations, and video games, Huitzilopochtli isn’t as popular today. The direct association with human sacrifice quickly eliminates a lot of genres whereas the colorful Feathered Serpent persona of Quetzalcoatl makes him a great candidate for reimagining in fantasy and even kids’ animations, books, and games.

One notable pop-culture mention of Huitzilopochtli is the trading card game Vampire: The Eterna Struggle where he is portrayed as an Aztec vampire. Given that the Aztecs literally fed Huitzilopochtli human hearts to keep him strong, this interpretation is hardly wrong.

Wrapping Up

As one of the most influential Aztec gods that drove the need for more conquests and capturing of enemies, Huitzilopochtli was at the heart of the Aztec empire. Worshipped with fervor and constantly offered sacrifices, the Aztec sun and war god was a powerful warrior whose influence can still be seen in present day Mexico.