Table of Contents

Ancient Greece was the cradle of some of the most important leaders of Western Civilization. By revisiting their accomplishments, we can develop a better grasp of the evolution of Greek history.

Before diving into the deep waters of Ancient Greek history, it’s important to know that there are different interpretations of the length of this period. Some historians say that Ancient Greece goes from the Greek Dark Ages, around 1200-1100 BC, to the death of Alexander the Great, in 323 BC. Other scholars argue that this period continues until the 6th century AD, thus including the rise of Hellenistic Greece and its fall and transformation into a Roman province.

This list covers Greek leaders from the 9th to the 1st century BC.

Lycurgus (9th-7th century BC?)

Lycurgus, a quasi-legendary figure, is credited for having instituted a code of laws that transformed Sparta into a military-oriented state. It’s believed that Lycurgus consulted the Oracle of Delphi (an important Greek authority), before implementing his reforms.

Lycurgus’ laws stipulated that after reaching the age of seven, every Spartan boy should leave their family’s home, to receive military-based education granted by the state. Such military instruction would continue uninterrupted for the next 23 years of the boy’s life. The Spartan spirit created by this way of life proved its value when Greeks had to defend their land from Persian invaders in the early 5th century BC.

In his pursuit of social equality, Lycurgus also created the ‘Gerousia’, a council formed by 28 male Spartan citizens, each of whom had to be at least 60 years old, and two kings. This body was able to propose laws but couldn’t implement them.

Under Lycurgus’ laws, any major resolution had to be first voted by a popular assembly known as the ‘Apella’. This decision-making institution was made up of Spartan male citizens that were at least 30 years old.

These, and many other institutions created by Lycurgus, were foundational to the rise of the country to power.

Solon (630 BC-560 BC)

Solon (born c. 630 BC) was an Athenian lawmaker, recognized for having instituted a series of reforms that laid the basis for democracy in Ancient Greece. Solon was elected archon (highest magistrate of Athens) between the years 594 and 593 BC. He then went on to abolish debt-slavery, a practice that had been largely used by wealthy families to subjugate the poor.

The Solonian Constitution also granted lower classes the right to attend the Athenian assembly (known as the ‘Ekklesia’), where common people could call their authorities to account. These reforms were supposed to limit the aristocrats’ power and bring more stability to the government.

Pisistratus (608 BC-527 BC)

Pisistratus (born c. 608 BC) ruled Athens from 561 to 527, though he was expelled from power several times during that period.

He was considered a tyrant, which in Ancient Greece was a term used specifically to refer to those who obtain political control by force. Nevertheless, Pisistratus respected most Athenian institutions during his rule and helped them to function more efficiently.

Aristocrats saw their privileges reduced during Pisistratus times, including some who were exiled, and had their lands confiscated and transferred to the poor. For these kinds of measures, Pisistratus is often considered an early example of a populist ruler. He did appeal to the common people, and in doing so, he ended up improving their economic situation.

Pisistratus is also credited for the first attempt to produce definitive versions of Homer’s epic poems. Considering the major role that Homer’s works played in the education of all Ancient Greeks, this might be the most important of Pisistratus’ achievements.

Cleisthenes (570 BC-508 BC)

Scholars frequently regard Cleisthenes (born c. 570 BC) as the father of democracy, thanks to his reforms to the Athenian Constitution.

Cleisthenes was an Athenian lawmaker who came from the aristocratic Alcmeonid family. Despite his origins, he didn’t support the idea, fostered by the upper classes, of establishing a conservative government, when Spartan forces successfully expelled the tyrant Hippias (Pisistratus’ son and successor) from Athens in 510 BC. Instead, Cleisthenes allied with the popular Assembly and changed the political organization of Athens.

The old system of organization, based on family relations, distributed citizens into four traditional tribes. But in 508 BC, Cleisthenes abolished these clans and created 10 new tribes that combined people from different Athenian localities, thus forming what would come to be known as ‘demes’ (or districts). From this time on, the exercise of public rights would depend strictly on being a registered member of a deme.

The new system facilitated interaction among citizens from different places and allowed them to directly vote for their authorities. Nevertheless, neither Athenian women nor slaves could benefit from these reforms.

Leonidas I (540 BC-480 BC)

Leonidas I (born c. 540 BC) was a king of Sparta, who is remembered for his notable participation in the Second Persian War. He ascended to the Spartan throne, somewhere between the years 490-489 BC, and became the designated leader of the Greek contingent when the Persian King Xerxes invaded Greece in 480 BC.

In the Battle of Thermopylae, Leonidas’ small forces stopped the advance of the Persian army (which is believed to have consisted of at least 80,000 men) for two days. After that, he ordered most of his troops to retreat. In the end, Leonidas and the 300 members of his Spartan guard of honor all died fighting off the Persians. The popular movie 300 is based on this.

Themistocles (524 BC-459 BC)

Themistocles (born c. 524 BC) was an Athenian strategist, best known for having advocated for the creation of a large naval fleet for Athens.

This preference for sea power wasn’t fortuitous. Themistocles knew that even though the Persians had been expelled from Greece in 490 BC, after the Battle of Marathon, the Persians still had the resources to organize a larger second expedition. With that threat on the horizon, Athens’ best hope was to build a navy powerful enough to stop the Persians at sea.

Themistocles struggled to convince the Athenian Assembly to pass this project, but in 483 it was finally approved, and 200 triremes were built. Not long after that the Persians attacked again and were roundly defeated by the Greek fleet in two decisive encounters: the Battle of Salamis (480 BC) and the Battle of Platea (479 BC). During these combats, Themistocles himself commanded the allied navies.

Considering that the Persians never fully recovered from that defeat, it’s safe to assume that by stopping their forces, Themistocles freed Western Civilization from the shadow of an Eastern conqueror.

Pericles (495 BC-429 BC)

Pericles (born c. 495 BC) was an Athenian statesman, orator, and general who led Athens approximately from 461 BC to 429 BC. Under his rule, the Athenian democratic system flourished, and Athens became the cultural, economic, and political center of Ancient Greece.

When Pericles came to power, Athens was already the head of the Delian League, an association of at least 150 city-states created during the Themistocles era and aimed at keeping the Persians out of the sea. Tribute was paid for the maintenance of the league’s fleet (formed mainly by Athen’s ships).

When in 449 BC peace was successfully negotiated with the Persians, many members of the league started doubting the need for its existence. At that point, Pericles intervened and proposed that the league restore Greek temples that were destroyed during the Persian invasion and patrol commercial sea routes. The league and its tribute subsisted, allowing the Athenian naval empire to grow.

With Athenian pre-eminence asserted, Pericles became involved in an ambitious building program that produced the Acropolis. In 447 BC, the construction of the Parthenon began, with the sculptor Phidias being responsible for decorating its interior. Sculpture was not the only art form to flourish in Periclean Athens; theater, music, painting, and other forms of art were promoted as well. During this period, Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides wrote their famous tragedies, and Socrates discussed philosophy with his followers.

Unfortunately, peaceful times don’t last forever, especially with a political adversary such as Sparta. In 446-445 BC Athens and Sparta had signed a 30-Year Peace treaty, but over time Sparta grew suspicious of the fast growth of its counterpart, leading to the outbreak of the Second Peloponnesian War in 431 BC. Two years after that, Pericles died, marking the end of the Athenian Golden Age.

Epaminondas (410 BC-362 BC)

Epaminondas (born c. 410 BC) was a Theban statesman and general, best known for briefly transforming the city-state of Thebes into the main political force of Ancient Greece in the early 4th century. Epaminondas was also distinguished for his use of innovative battlefield tactics.

After winning the Second Peloponnesian War in 404 BC, Sparta started to subjugate different Greek city-states. However, when the time to march against Thebes came in 371 BC, Epaminondas defeated the 10,000 strong forces of King Cleombrotus I at the Battle of Leuctra, with just 6,000 men.

Before the battle took place, Epaminondas had discovered that the Spartan strategists were still using the same conventional formation as the rest of the Greek states. This formation was constituted by a fair line only a few ranks deep, with a right wing comprising the best of the troops.

Knowing what Sparta would do, Epaminondas opted for a different strategy. He gathered his most experienced warriors on his left wing to a depth of 50 ranks. Epaminondas planned to annihilate the Spartan elite troops with the first assault and put the rest of the enemy’s army to rout. He succeeded.

In the following years, Epaminondas would continue to defeat Sparta (now allied with Athens) on several occasions, but his death in the Battle of Mantinea (362 BC) would put an early end to the preeminence of Thebes.

Timoleon (411 BC-337 BC)

In 345 BC, an armed conflict for political preeminence between two tyrants and Carthage (the Phoenician city-state) was bringing destruction upon Syracuse. Desperate in this situation, a Syracusan council sent an aid request to Corinth, the Greek city that had founded Syracuse in 735 BC. Corinth accepted to send help and chose Timoleon (born c.411 BC) to lead a liberation expedition.

Timoleon was a Corinthian general who had already helped to fight despotism in his city. Once in Syracuse, Timoleon expelled the two tyrants and, against all odds, defeated the 70,000 strong forces of Carthage, with less than 12,000 men in the Battle of Crimisus (339 BC).

After his victory, Timoleon restituted democracy in Syracuse and other Greek cities from Sicily.

Phillip II of Macedon (382 BC-336 BC)

Before the arrival of Philip II (born c. 382 BC) to the Macedonian throne in 359 BC, Greeks regarded Macedon as a barbaric kingdom, not strong enough to represent a threat to them. However, in less than 25 years, Philip conquered Ancient Greece and became the president (‘hēgemōn’) of a confederation that included all Greek states, except for Sparta.

With the Greek armies at his disposal, in 337 BC Philip began to organize an expedition to attack the Persian Empire, but the project was interrupted one year later when the king was assassinated by one of his bodyguards.

However, plans for the invasion did not fall into oblivion, because Philip’s son, a young warrior called Alexander, was also interested in leading the Greeks beyond the Aegean Sea.

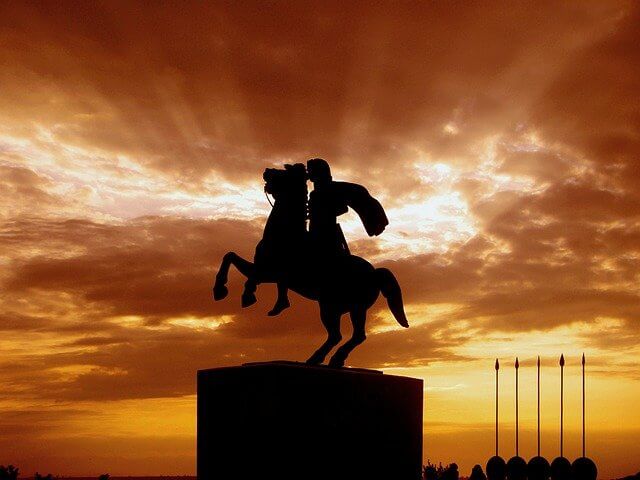

Alexander the Great (356 BC-323 BC)

When he was 20 years old, Alexander III of Macedon (born c. 356 BC) succeeded King Philip II to the Macedonian throne. Soon after, some Greek states began an insurrection against him, perhaps considering the new ruler to be less dangerous than the last. To prove them wrong, Alexander defeated the insurgents on the battlefield and razed Thebes.

Once the Macedonian dominance was reasserted over Greece, Alexander resumed his father’s project of invading the Persian empire. For the next 11 years, an army constituted by both Greeks and Macedonians would march eastward, defeating one foreign army after another. By the time Alexander died at just age 32 (323 BC), his empire stretched from Greece to India.

The plans that Alexander had for the future of his rising empire are still a matter of discussion. But had the last Macedonian conqueror not died so young, he would probably have continued expanding his domains.

Regardless, Alexander the Great is recognized for having considerably extended the limits of the known world of his time.

Pyrrhus of Epirus (319 BC-272 BC)

After the death of Alexander the Great, his five closest military officers split the Greco-Macedonian empire into five provinces and appointed themselves as governors. Within a couple of decades, subsequent divisions would leave Greece at the edge of dissolution. Still, during these times of decadence, the military victories of Pyrrhus (born c. 319 BC) represented a brief interval of glory for the Greeks.

King Pyrrhus of Epirus (a Northwestern Greek kingdom) defeated Rome in two battles: Heracles (280 BC) and Ausculum (279 BC). According to Plutarch, the enormous number of casualties that Pyrrhus received in both encounters made him say: “If we are victorious in one more battle with the Romans, we shall be utterly ruined”. His costly victories indeed led Pyrrhus to a disastrous defeat at the hands of the Romans.

The expression “Pyrrhic victory” comes from here, meaning a victory that has such a terrible toll on the victor that it’s almost equivalent to a defeat.

Cleopatra (69 BC-30 BC)

Cleopatra (born c. 69 BC) was the last Egyptian queen, an ambitious, well-educated ruler, and a descendant of Ptolemy I Soter, the Macedonian general who took over Egypt after the death of Alexander the Great and founded the Ptolemaic dynasty. Cleopatra also played a notorious role in the political context that preceded the rise of the Roman Empire.

Evidence suggests that Cleopatra knew at least nine languages. She was fluent in Koine Greek (her mother tongue) and Egyptian, which curiously enough, no other Ptolemaic regent besides her took the effort of learning. Being polyglot, Cleopatra could speak with rulers from other territories without the assistance of an interpreter.

In a time characterized by political upheaval, Cleopatra successfully maintained the Egyptian throne for approximately 18 years. Her affairs with Julius Caesar and Mark Antony also allowed Cleopatra to expand her domains, acquiring different territories such as Cyprus, Libya, Cilicia, and others.

Conclusion

Each of these 13 leaders represents a turning point in the history of Ancient Greece. All of them struggled to defend a particular vision of the world, and many perished in doing so. But in the process, these characters also laid the foundations for the future development of Western Civilization. Such actions are what make these figures still relevant for an accurate understanding of Greek history.