Table of Contents

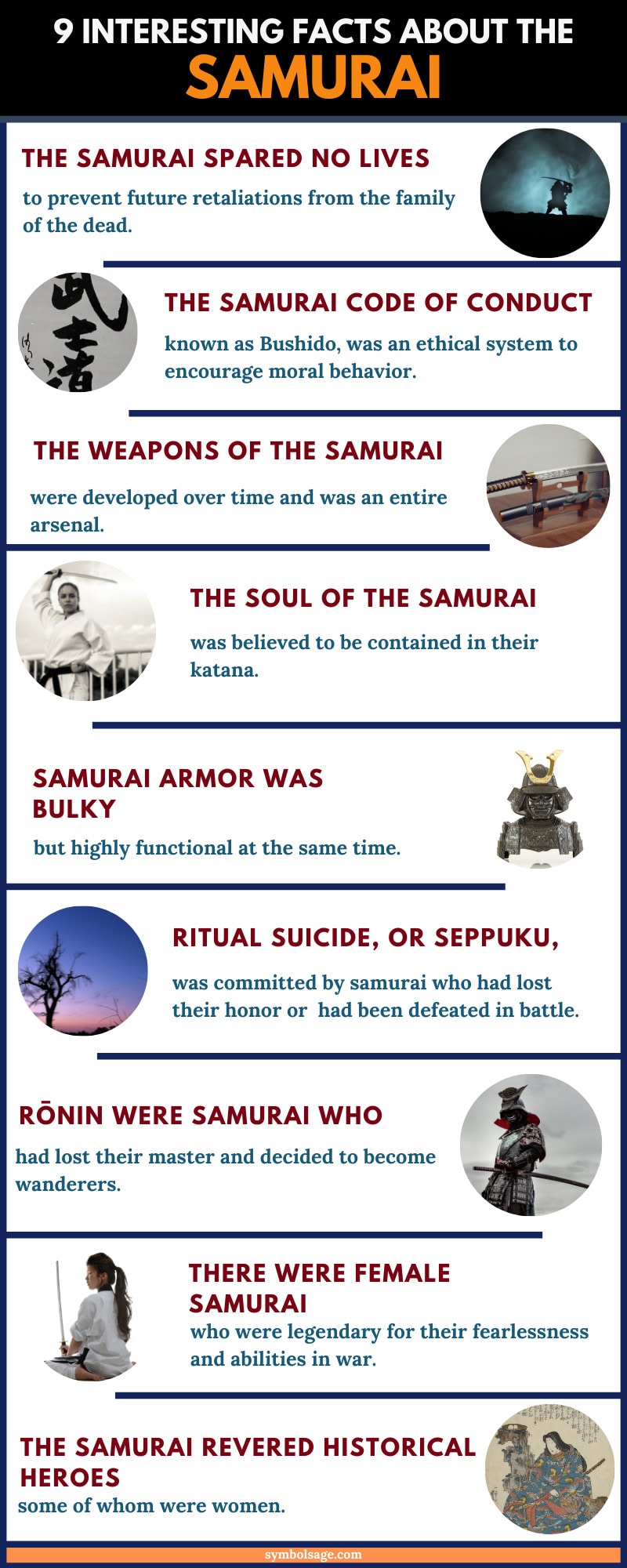

The Japanese samurai stand among the most legendary warriors in history, known for their strict code of conduct, intense loyalty, and stunning fighting skills. And yet, there is much about the samurai that most people don’t know.

Medieval Japanese society followed a strict hierarchy. The tetragram shi-no-ko-sho stood for the four social classes, in descending order of importance: warriors, farmers, artisans, and tradespeople. The samurai were members of the upper class of warriors, even though not all of them were fighters.

Let’s take a look at some of the most interesting facts about the Japanese samurai, and why they continue to inspire our imagination even today.

1. There was a historical reason for the samurai’s lack of mercy.

The samurai are known for sparing no lives when seeking revenge. Entire families are known to have been put to the sword by vengeful samurai after the transgression of only one member. While senseless and brutal from today’s point of view, this has to do with the fight between the different clans. The bloody tradition started with two clans in particular – the Genji and the Taira.

In 1159 AD, during the so-called Heiji Insurrection, the Taira family rose to power led by their patriarch Kiyomori. However, he made an error by sparing the lives of his enemy Yoshitomo’s (of the Genji clan) infant children. Two of Yoshitomo’s boys would grow up to become the legendary Yoshitsune and Yoritomo.

They were great warriors who fought the Taira until their last breath, eventually ending their power forever. This was not a straightforward process, and from the warring factions’ point of view, Kiyomori’s mercy cost thousands of lives lost during the cruel Genpei War (1180-1185). From that point onward, samurai warriors adopted the habit of slaughtering every member of their enemies’ families to prevent further conflict.

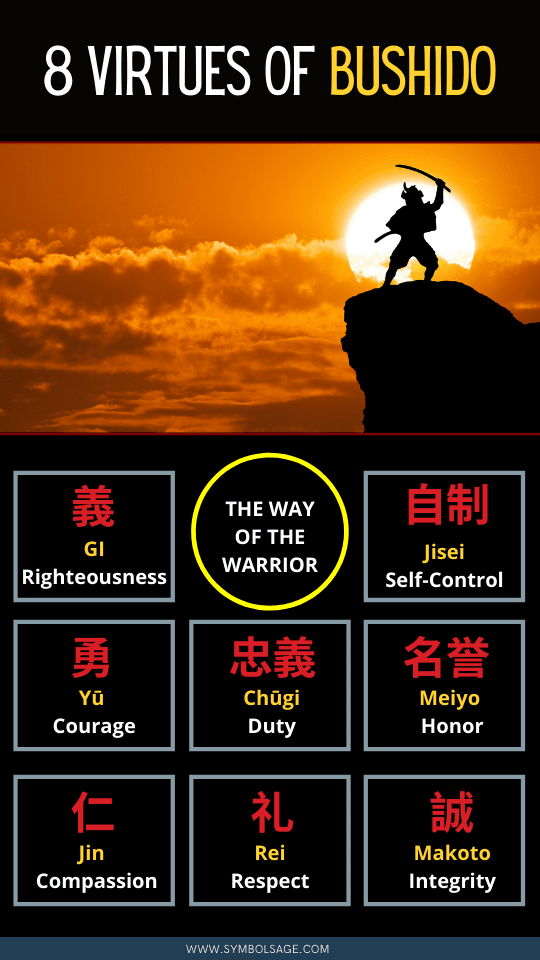

2. They followed a strict code of honor called bushido.

Despite what was just said, the samurai were not entirely ruthless. In fact, all their actions and conducts were shaped by the code of bushidō, a composite word that can be translated as ‘way of the warrior’. It was an entire ethical system designed to maintain the prestige and reputation of samurai warriors, and it was handed down from mouth to mouth within the warrior aristocracy of Medieval Japan.

Drawing extensively from Buddhist philosophy, bushido taught the samurai to calmly trust in Fate and to submit to the Inevitable. But Buddhism also prohibits violence in any form. Shintoism, in turn, prescribed loyalty to the rulers, reverence for the memory of ancestors, and self-knowledge as a way of life.

Bushidō was influenced by these two schools of thought, as well as by Confucianism, and became an original code of moral principles. The prescriptions of bushidō include the following ideals among many others:

- Rectitude or justice.

- “To die when it is right to die, to strike when it is right to strike”.

- Courage, defined by Confucius as acting upon what is right.

- Benevolence, being thankful, and not forgetting those who helped the samurai.

- Politeness, as the samurai were required to maintain good manners in every situation.

- Veracity and Sincerity, for in times of lawlessness, the only thing that protected a person was their word.

- Honor, the vivid consciousness of personal dignity and worth.

- The duty of Loyalty, essential in a Feudal system.

- Self-Control, which is the counterpart of Courage, not acting upon what is rationally wrong.

3. Throughout their history, the samurai developed an entire arsenal.

Bushidō students had a wide array of topics in which they were schooled: fencing, archery, jūjutsu, horsemanship, spear fighting, war tactics, calligraphy, ethics, literature, and history. But they are most known for the impressive number of weapons they used.

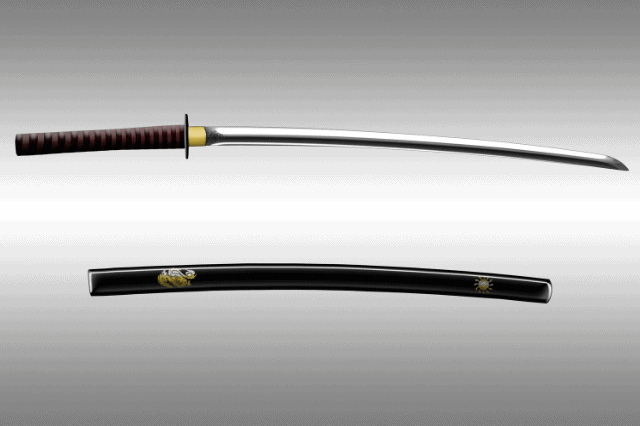

Of course, the most well-known of these is the katana, which we’ll cover below. What the samurai called daishō (literally big-small) was the coupling of a katana and a smaller blade called a wakizashi. Only warriors who abode by the code of samurai were permitted to wear the daishō.

Another popular samurai blade was the tantō, a short, sharp dagger that sometimes women carried for self-defense. A long blade fastened to the tip of a pole was called naginata, popular especially in the late 19th century, or the Meiji era. Samurai also used to carry a sturdy knife called kabutowari, literally helmet-breaker, which needs no explanation.

Finally, the asymmetric longbow used by horseback archers was known as yumi, and a whole array of arrowheads was invented to be used with it, including some arrows intended to whistle while airborne.

4. The samurai soul was contained in their katana.

But the main weapon the samurai wielded was the katana sword. The first samurai swords were known as chokuto, a straight, thin blade that was very light and fast. During the Kamakura period (12th-14th centuries) the blade became curved and was called tachi.

Eventually, the classic curved single-edged blade called katana appeared and became closely associated with the samurai warriors. So closely, that warriors believed their soul was inside the katana. So, their fates were connected, and it was crucial that they took care of the sword, just as it took care of them in battle.

5. Their armor, although bulky, was highly functional.

The samurai were trained in close-quarters combat, stealth, and jūjutsu, which is a martial art based on grappling and using the opponent’s force against them. Clearly, they needed to be able to move freely and benefit from their agility in battle.

But they also needed heavy padding against blunt and sharp weapons and enemy arrows. The result was an ever-evolving set of samurai armor, mainly consisting of an elaborate ornated helmet called a kabuto, and a body armor that received many names, the most generic being dō-maru.

Dō was the name of the padded plates that composed the costume, made out of leather or iron scales, treated with a lacquer that prevented weathering. The different plates were bound together by silk laces. The result was a very light but protecting armor that let the user run, climb, and jump without effort.

6- Rebel samurai were known as Rōnin.

One of the commandments of the bushidō code was Loyalty. Samurai pledged allegiance to a master, but when their master died, they would often become wandering rebels, rather than finding a new lord or committing suicide. The name of these rebels was rōnin, meaning wave-men or wandering men because they never remained in a single place.

Ronin would often offer their services in exchange for money. And although their reputation was not as high as other samurai’s, their abilities were sought after and highly regarded.

7. There were female samurai.

As we have seen, Japan had a long history of being ruled by powerful Empresses. However, from the 8th century onwards the political power of women declined. By the time of the great civil wars of the 12th century, female influence on state decisions had become nearly entirely passive.

Once the samurai started to rise into prominence, however, the opportunities for women to follow the bushidō also increased. One of the best-known female samurai warriors of all time was Tomoe Gozen. She was the female companion of the hero Minamoto Kiso Yoshinaka and fought beside him at his last battle at Awazu in 1184.

She is said to have fought bravely and fiercely, right until there were only five people left in the army of Yoshinaka. Seeing that she was a woman, Onda no Hachiro Moroshige, a strong samurai and opponent of Yoshinaka, decided to spare her life and let her go. But instead, when Onda came riding up with 30 followers, she dashed into them and flung herself upon Onda. Tomoe grappled him, dragged him from his horse, pressed him calmly against the pommel of her saddle, and cut his head off.

Naturally, Japan’s society during the time of the samurai was still largely patriarchal but even then, strong women found their way onto the battlefield when they wanted to.

8. They committed ritual suicide.

According to bushidō, when a samurai warrior lost their honor or was defeated in battle, there was only one thing to do: seppuku, or ritual suicide. This was an elaborate and highly ritualized process, done before many witnesses that could later tell others about the bravery of the late samurai.

The samurai would make a speech, stating why they deserved to die in such a way, and afterward would lift the wakizashi with both hands and thrust it into their abdomen. Death by self-disembowelment was considered extremely respectable and honorable.

9. One of the greatest heroes of the samurai was a woman.

The samurai revered historical figures who had fought in battle and showed bravery, rather than rule from the comfort of their castles. These figures were their heroes and were highly respected.

Perhaps the most interesting of those was Empress Jingū, a fierce ruler who led the invasion of Korea while pregnant. She fought alongside the samurai and became known as one of the fiercest female samurai to have lived. She returned to Japan after three years, having achieved victory in the peninsula. Her son went on to become Emperor Ōjin, and after his death, he was deified as the war god Hachiman.

Empress Jingū’s reign started in 201 C.E., after the death of her husband, and lasted for almost seventy years. The driving force of her military exploits was allegedly the search for revenge on the people who had murdered Emperor Chūai, her husband. He had been killed in battle by rebels during a military campaign where he sought to expand the Japanese Empire.

Empress Jingū inspired a wave of female samurai’s, who followed in her wake. Her favored tools, the kaiken dagger and the naginata sword, would become some of the most popular weapons used by female samurai.

Wrapping Up

Samurai warriors were members of the higher classes, extremely cultivated and well trained, and they followed a strict code of honor. As long as anyone followed the bushidō, it made no difference if they were men or women. But whoever lived by bushidō, had to die by bushidō too. Hence the stories of bravery, honor, and severity that have lasted until our days.