Table of Contents

Goethe once expressed his judgment about Persian literature:

“The Persians had seven great poets, each of whom is a little greater than me.”

Goethe

And Goethe was right indeed. Persian poets had a talent for presenting the full spectrum of human emotions, and they did it with such skill and precision that they could fit it into just a couple of verses.

Few societies ever reached these heights of poetic development like the Persians. Let’s get into Persian poetry by exploring the greatest Persian poets and learning what makes their work so powerful.

Types of Persian Poems

Persian poetry is very versatile and contains numerous styles, each unique and beautiful in its own way. There are several types of Persian poetry, including the following:

1. Qaṣīdeh

Qaṣīdeh is a longer monorhyme poem, which usually never exceeds a hundred lines. Sometimes it is panegyric or satirical, instructive, or religious, and sometimes elegiac. The most famous poets of Qaṣīdeh were the Rudaki, followed by Unsuri, Faruhi, Enveri, and Kani.

2. Gazelle

Gazelle is a lyrical poem that’s almost identical in form and rhyme order to the Qaṣīdeh but is more elastic and lacks a suitable character. It usually does not exceed fifteen verses.

Persian poets perfected the Gazelle in form and content. In the gazelle, they sang about topics such as eternal love, the rose, the nightingale, beauty, youth, eternal truths, the meaning of life, and the essence of the world. Saadi and Hafiz produced masterpieces in this form.

3. Rubaʿi

Rubaʿi (also known as a quatrain) contains four lines (two couplets) with AABA or AAAA rhyming schemes.

Ruba’i is the shortest of all Persian poetic forms and gained world fame through the verses of Omar Khayyam. Almost all Persian poets used Rubaʿi. The Rubaʿi demanded perfection of form, conciseness of thought, and clarity.

4. Mesnevia

Mesnevia (or rhyming couplets) consist of two half-verses with the same rhyme, with each couplet having a different rhyme.

This poetic form was used by Persian poets for compositions that spanned thousands of verses and represented many epics, romantics, allegories, didactics, and mystical songs. Scientific experiences were also presented in Mesnevian form, and it is a pure product of the Persian spirit.

Famous Persian Poets and Their Works

Now that we have learned more about Persian poetry, let’s take a peek into the lives of some of the best Persian poets and savor their beautiful poetry.

1. Hafez – The Most Influential Persian Writer

Although no one is quite sure what year the great Persian poet Hafiz was born, most contemporary writers have determined that it was around 1320. It was also around sixty years after Hulagu, the grandson of Genghis Khan, looted and burned Baghdad and fifty years after the death of the poet Jelaluddin Rumi.

Hafiz was born, bred, and buried in beautiful Shiraz, a city that miraculously escaped the looting, raping, and burning that befell most of Persia during the Mongol invasions of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. He was born Khwāja Shams-ud-Dīn Muḥammad Ḥāfeẓ-e Shīrāzī but is known by the pen name Hafez or Hafiz, which means the ‘memorizer’.

As the youngest of three sons, Hafiz grew up in a warm family atmosphere and, with his profound sense of humor and kind demeanor, was a joy to his parents, brothers, and friends.

From his childhood, he showed great interest in poetry and religion.

The name “Hafiz” signified both an academic title in theology and an honorary title that was given to one who knew the entire Koran by heart. Hafiz tells us in one of his poems that he memorized fourteen different versions of the Koran.

It is said that Hafiz’s poetry would cause a veritable frenzy in all who read it. Some would label his poetry as divine madness or “God-intoxication,” an ecstatic state that some still believe today can occur as a result of unbridled absorption of the poetic outpourings of the maestro Hafiz.

The Love of Hafiz

Hafiz was twenty-one years old and working in a bakery where one day, he was asked to deliver bread to an affluent part of town. As he walked past a luxurious house, his eyes met the beautiful eyes of a young woman who was watching him from the balcony. Hafiz was so enthralled by the beauty of that lady that he fell hopelessly in love with her.

The young woman’s name was Shakh-i-Nabat (“Sugar Cane”), and Hafiz learned that she was bound to marry a prince. Of course, he knew that his love for her had no prospects, but that didn’t stop him from writing poems about her.

His poems were read and discussed in the wineries of Shiraz, and soon, people throughout the city, including the lady herself, knew of his passionate love for her. Hafiz thought about the beautiful lady day and night and hardly slept or ate.

Suddenly, one day, he remembered a local legend about a Master Poet, Baba Kuhi, who some three hundred years earlier had made a solemn promise that after his death anyone who would stay awake at his grave for forty consecutive nights would acquire the gift of immortal poetry and that the most ardent desire of his heart will be fulfilled.

That same night, after finishing work, Hafiz walked four miles outside the city to Baba Kuhi’s grave. All night he sat, stood, and walked around the grave, begging Baba Kuhi for help in fulfilling his greatest wish – to get the hand and love of the beautiful Shakh-i-Nabat.

With each passing day, he became more and more exhausted and weak. He moved and functioned like a man in a deep trance.

Finally, on the fortieth day, he went to spend the last night by the grave. As he was passing by his beloved’s home, she suddenly opened the door and approached him. Throwing her arms around his neck, she told him, between hasty kisses, that she would rather marry a genius than a prince.

Hafiz’s successful forty-day vigil became known to everyone in Shiraz and made him a kind of hero. Despite his profound experience with God, Hafiz still had an enthusiastic love for Shakh-i-Nabat.

Although he later married another woman who bore him a son, the beauty of Shakh-i-Nabat would always inspire him as a reflection of the perfect beauty of God. She was, after all, the true impetus that led him into the arms of his Divine Beloved, changing his life forever.

One of his most well-known poems goes as follows:

Days of Spring

The days of Spring are here! the eglantine,

The rose, the tulip from the dust have risen–

And thou, why liest thou beneath the dust?

Like the full clouds of Spring, these eyes of mine

Shall scatter tears upon the grave thy prison,

Till thou too from the earth thine head shalt thrust.

Hafiz

2. Saadi – Poet with a Love for Humankind

Saadi Shirazi is known for his social and moral perspectives on life. In every sentence and every thought of this great Persian poet, you can find traces of impeccable love for humankind. His work Bustan, a collection of poems, made the Guardian’s list of 100 greatest books of all time.

Belonging to a certain nation or religion was never a primary value for Saadi. The object of his eternal concern was only a human, regardless of his color, race, or geographical area in which they reside. After all, this is the only attitude we can expect from a poet whose verses have been uttered for centuries:

People are parts of one body, they are created from the same essence. When one part of the body gets sick, other parts do not remain in peace. You, who do not care about other people’s troubles, are not worthy to be called human.

Saadi wrote of love tempered by tolerance, which is why his poems are attractive and close to every person, in any climate, and any period. Saadi is a timeless writer, awfully close to the ears of each of us.

Saadi’s firm and almost undeniable attitude, the beauty and pleasantness that can be felt in his stories, his loveliness, and his penchant for special expression, (while criticizing various social problems) offer him virtues that hardly anyone in the history of literature possessed at once.

Universal Poetry That Touches Souls

While reading Saadi’s verses and sentences, you get the feeling that you are traveling through time: from Roman moralists and storytellers to contemporary social critics.

Saadi’s influence extends beyond the period in which he lived. Saadi is a poet of both the past and the future and belongs to both the new and old worlds and he was also able to reach great fame beyond the Muslim world.

But why is that so? Why were all those Western poets and writers amazed by Saadi’s way of expression, his literary style, and the content of his poetic and prose books, even though the Persian language in which Saadi wrote was not their native language?

Saadi’s works are full of symbols, stories, and themes from everyday life, close to every person. He writes about the sun, the moonlight, the trees, their fruits, their shadows, about animals, and their struggles.

Saadi enjoyed nature and its charms and beauty, that’s why he wanted to find the same harmony and brilliance in people. He believed that each person could carry the burden of their society in accordance with their capabilities and abilities, and that is precisely why everyone has the duty to participate in the construction of social identity.

He deeply despised all those who neglected the social aspects of their existence and thought that they would achieve some form of individual prosperity or enlightenment.

The Dancer

From the Bustan I heard how, to the beat of some quick tune,

There rose and danced a Damsel like the moon,

Flower-mouthed and Pâri-faced; and all around her

Neck-stretching Lovers gathered close; but soon A flickering lamp-flame caught her skirt, and set

Fire to the flying gauze. Fear did beget

Trouble in that light heart! She cried amain.

Quoth one among her worshipers, “Why fret, Tulip of Love? Th’ extinguished fire hath burned

Only one leaf of thee; but I am turned

To ashes–leaf and stalk, and flower and root–

By lamp-flash of thine eyes!”–“Ah, Soul concerned “Solely with self!”–she answered, laughing low,

“If thou wert Lover thou hadst not said so.

Who speaks of the Belov’d’s woe is not his

Speaks infidelity, true Lovers know!”

Saadi

3. Rumi – The Poet of Love

Rumi was a Persian and Islamic philosopher, theologian, jurist, poet, and Sufi mystic from the 13th century. He is considered one of the greatest mystical poets of Islam and his poetry is no less influential to this day.

Rumi is one of the great spiritual teachers and poetic geniuses of mankind. He was the founder of the Mawlavi Sufi order, the leading Islamic mystical brotherhood.

Born in today’s Afghanistan, which was then part of the Persian Empire, to a family of scholars. Rumi’s family had to take refuge from the Mongol invasion and destruction.

During that time, Rumi and his family traveled to many Muslim countries. They completed the pilgrimage to Mecca, and finally, somewhere between 1215 and 1220, settled in Anatolia, which was then part of the Seljuk Empire.

His father Bahaudin Valad, besides being a theologian, was also a jurist and a mystic of unknown lineage. His Ma’rif, a collection of notes, diary observations, sermons, and unusual accounts of visionary experiences, shocked most conventionally learned people who tried to understand him.

Rumi and Shams

Rumi’s life was quite ordinary for a religious teacher – teaching, meditating, helping the poor, and writing poetry. Eventually, Rumi became inseparable from Shams Tabrizi, another mystic.

Although their intimate friendship remains a thing of mystery, they spent several months together without any human needs, engrossed in the sphere of pure conversation and companionship. Unfortunately, that ecstatic relationship caused trouble in the religious community.

Rumi’s disciples felt neglected, and sensing trouble, Shams disappeared as suddenly as he had appeared. At the time of Shams’ disappearance, Rumi’s transformation into a mystical artist began. He became a poet; he started listening to music and singing to process his loss.

There is plenty of pain in his verses:

“A wound is where the light enters you.”

Rumi

Or:

“I want to sing like a bird, not caring who is listening, or what they think.”

Rumi

On The Day of My Death

On the day of (my) death when my coffin is going (by), don’t

imagine that I have (any) pain (about leaving) this world.

Don’t weep for me, and don’t say, “How terrible! What a pity!

(For) you will fall into the error of (being deceived by) the Devil,

(and) that would (really) be a pity!

When you see my funeral, don’t say, “Parting and separation!

(Since) for me, that is the time for union and meeting (God).

(And when) you entrust me to the grave, don’t say,

“Good-bye! Farewell!” For the grave is (only) a curtain for

(hiding) the gathering (of souls) in Paradise.

When you see the going down, notice the coming up. Why should

there be (any) loss because of the setting of the sun and moon?

It seems like a setting to you, but it is rising.

The tomb seems like a prison, (but) it is the liberation of the soul.

What seed (ever) went down into the earth which didn’t grow

(back up)? (So), for you, why is there this doubt about the human

“seed”?

What bucket (ever) went down and didn’t come out full? Why

should there be (any) lamenting for the Joseph of the soul6 because

of the well?

When you have closed (your) mouth on this side, open (it) on

that side, for your shouts of joy will be in the Sky beyond place

(and time).

Rumi

Only Breath

Not Christian or Jew or Muslim, not Hindu

Rumi

Buddhist, sufi, or zen. Not any religion

or cultural system. I am not from the East

or the West, not out of the ocean or up

from the ground, not natural or ethereal, not

composed of elements at all. I do not exist,

am not an entity in this world or in the next,

did not descend from Adam and Eve or any

origin story. My place is placeless, a trace

of the traceless. Neither body or soul.

I belong to the beloved, have seen the two

worlds as one and that one call to and know,

first, last, outer, inner, only that

breath breathing human being.

4. Omar Khayyam – Quest for Knowledge

Omar Khayyam was born in Nishapur, in northeastern Persia. Information about the year of his birth is not entirely dependable, but most of his biographers agree that it was 1048.

He died in 1122, in his hometown. He was buried in the garden because the clergy at the time forbade him to be buried in a Muslim, cemetery as a heretic.

The word “Khayyam” means tent maker and probably refers to his family’s trade. Since Omar Khayyam himself was a famous astronomer, physicist, and mathematician, he studied the humanities and exact sciences, especially astronomy, meteorology, and geometry, in his native Nishapur, then in Balkh, which was an important cultural center at the time.

During his lifetime, he engaged in several different pursuits, including reforming the Persian calendar, on which he worked as the head of a group of scientists from 1074 to 1079.

He is also famous is his treatise on algebra, which was published in the middle of the 19th century in France, and in 1931 in America.

As a physicist, Khayyam wrote, among other things, works on the specific gravity of gold and silver. Although the exact sciences were his primary scholarly preoccupation, Khayyam also mastered the traditional branches of Islamic philosophy and poetry.

The times in which Omar Khayyam lived were restless, uncertain, and filled with quarrels and conflicts between different Islamic sects. However, he did not care about sectarianism or any other theological quarrels, and being among the most enlightened personalities of that time, was alien to all, especially religious fanaticism.

In the meditative texts, he wrote down during his life, the marked tolerance with which he observed human misery, as well as his understanding of the relativity of all values, is something that no other writer of his time has achieved.

One can easily see the sadness and pessimism in his poetry. He believed that the only safe thing in this world is uncertainty about the basic questions of our existence and human destiny in general.

For Some We Loved

For some we loved, the loveliest and the best

Omar Khayyam

That from His vintage rolling Time hath pressed,

Have drunk the Cup a round or two before,

And one by one crept silently to rest.

Come Fill the Cup

Come, fill the cup, and in the fire of spring

Omar Khayyam

Your winter garment of repentance fling.

The bird of time has but a little way

To flutter – and the bird is on the wing.

Wrapping Up

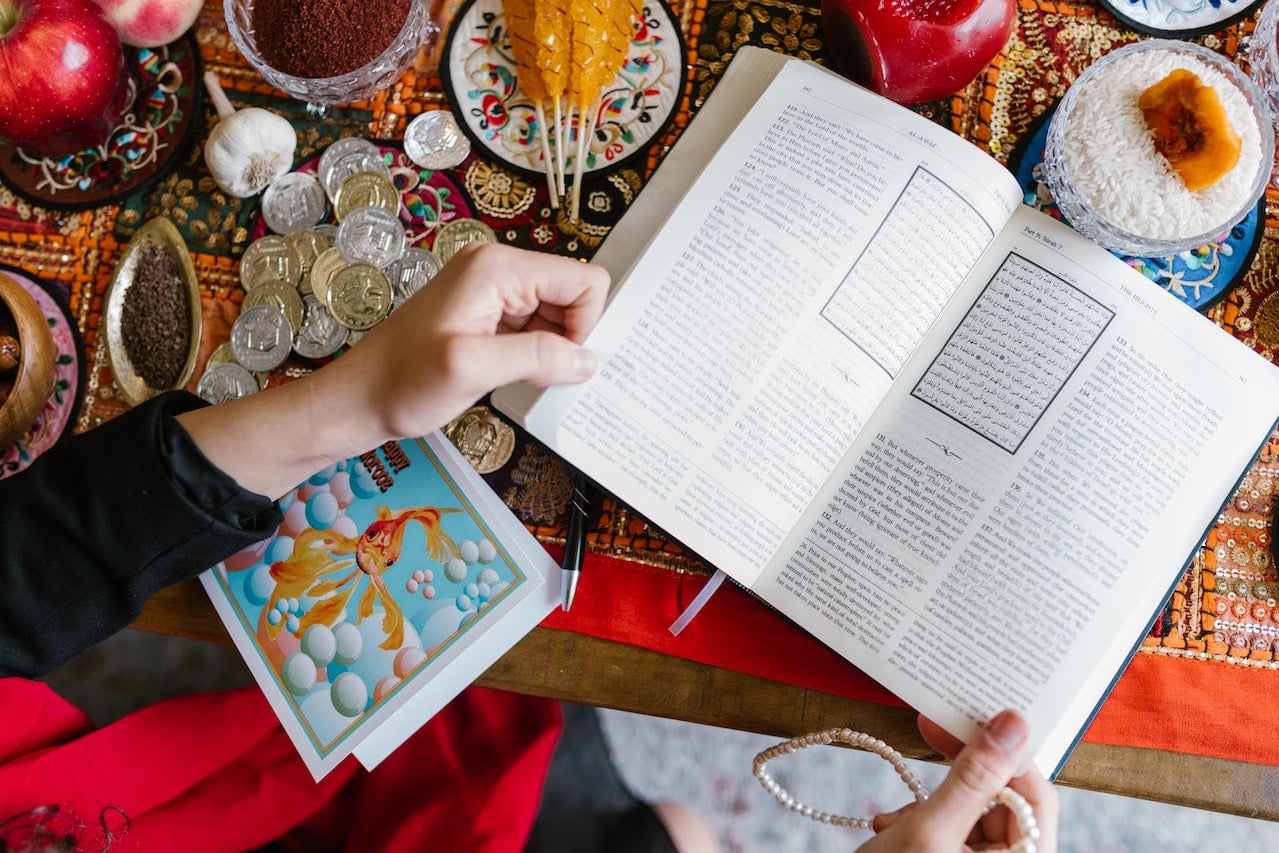

Persian poets are known for their intimate portrayal of what it means to love, suffer, laugh, and live, and their skill in portraying the human condition is unmatched. Here, we gave you an overview of some 5 of the most important Persian poets, and we hope their works touched your soul.

Next time you’re longing for something that will make you experience the full intensity of your emotions, pick up a poetry book by any of these masters, and we are sure you will enjoy them just as much as we did.