Australia is a land of superlatives – it has the world’s oldest continuous culture, the largest monolith, the most venomous snake, the largest coral reef system in the world, and many more.

Located between the Pacific and Indian oceans, in the Southern hemisphere of the world, the country (which is also a continent and an island) has a population of around 26 million people. Despite being far from Europe, the history of the two continents is dramatically intertwined – after all, modern Australia began as a British colony.

In this comprehensive article, let’s take a look at Australian history, from ancient times to the modern-day.

An Ancient Land

Before the western world’s interest in the southern continent, Australia was home to its Indigenous people. No one knows exactly when they came to the island, but their migration is believed to date back around 65,000 years.

Recent research has revealed that Indigenous Australians were among the first to migrate out of Africa and to arrive and roam in Asia before finding their way to Australia. This makes the Australian Aborigines the world’s oldest continuous culture. There were numerous Aboriginal tribes, each with its distinct culture, customs, and language.

By the time the Europeans invaded Australia, the Aboriginal population was estimated to range between 300,000 to 1,000,000 people.

In the Search of the Mythical Terra Australis Incognita

Australia was discovered by the West in the early 17th century when the different European powers were in a race to see who would colonize the wealthiest territory in the Pacific. However, it doesn’t mean that other cultures didn’t reach the continent before that.

- Other voyagers may have landed on Australia before the Europeans.

As some Chinese documents seem to suggest, China’s control over the South Asian sea might have led to a landing in Australia as far back as the early 15th century. There are also reports of Muslim voyagers who navigated within a range of 300 miles (480 km) of the Northern coasts of Australia at a similar period.

- A mythical land mass in the south.

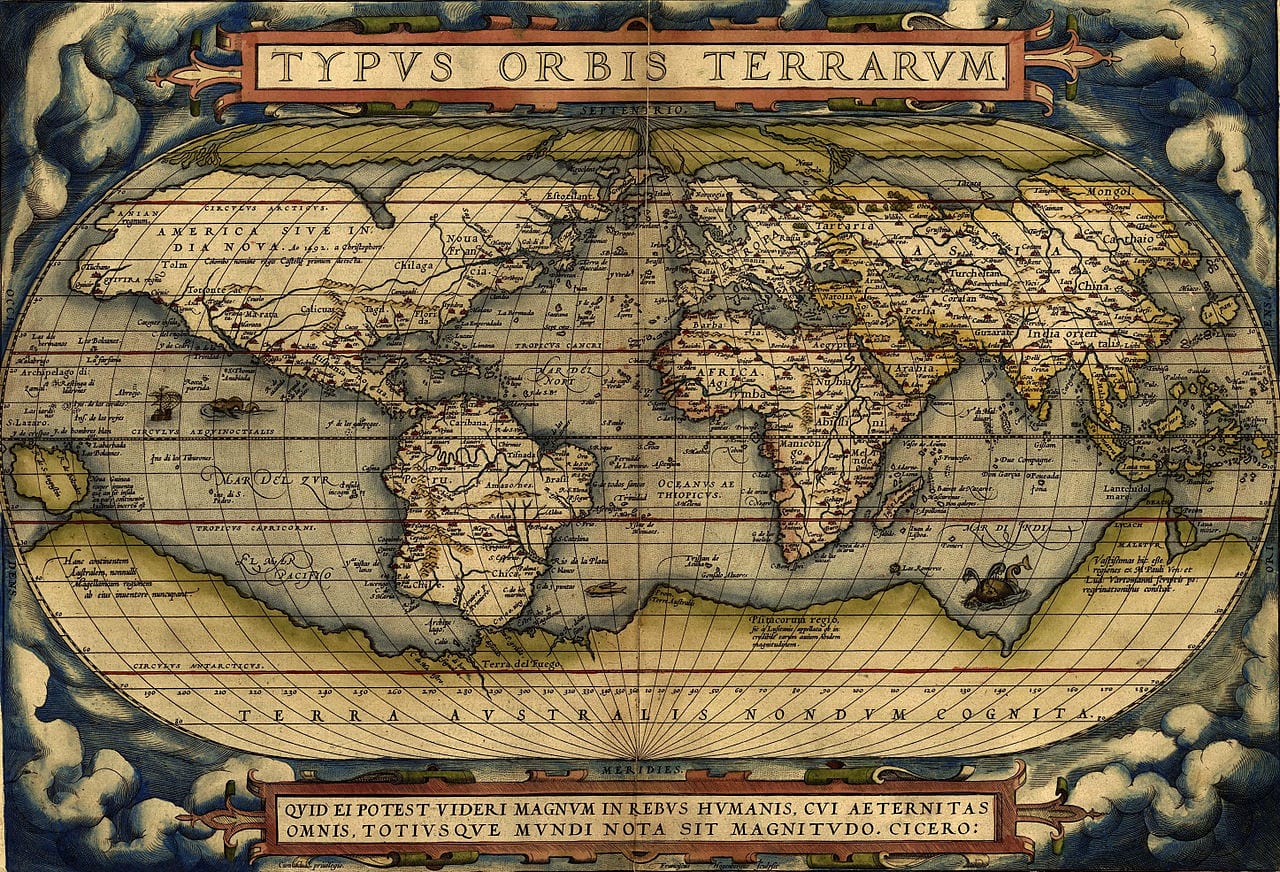

But even way before that time, a mythical Australia was already brewing in the imaginations of some people. Brought up for the first time by Aristotle, the concept of a Terra Australis Incognita supposed the existence of an enormous yet unknown mass of land somewhere to the south, an idea that Claudius Ptolemy, the famous Greek geographer, also replicated during the 2nd century AD.

- Cartographers add a southern land mass to their maps.

Later on, a renewed interest in the Ptolemaic works led European cartographers from the 15th century onward to add a gigantic continent at the bottom of their maps, even though such a continent had still not been discovered.

- Vanuatu is discovered.

Subsequently, guided by the belief in the existence of the legendary landmass, several explorers claimed to have found Terra Australis. Such was the case of the Spanish navigator Pedro Fernandez de Quirós, who decided to name a group of islands he discovered during his 1605 expedition to the Southwestern Asian sea, calling them Del Espíritu Santo (present-day Vanuatu).

- Australia remains unknown to the west.

What Quirós didn’t know was that approximately 1100 miles to the west was an unexplored continent that met many of the features attributed to the legend. However, it wasn’t in his destiny to uncover its presence. It was the Dutch navigator Willem Janszoon, who in early 1606, reached Australian coasts for the first time.

Early Makassarese Contact

The Dutch called the recently discovered island New Holland but didn’t spend much time exploring it, and therefore weren’t able to realize the actual proportions of the land found by Janszoon. More than a century and a half would pass before Europeans properly investigated the continent. Nevertheless, during this period, the island would become a common destiny for another non-western group: the Makassarese trepangers.

- Who were the Makasserese?

The Makassarese are an ethnic group that comes originally from the southwest corner of the Sulawesi island, in modern-day Indonesia. Being great navigators, the Makassarese people were able to establish a formidable Islamic empire, with a great naval force, between the 14th and the 17th centuries.

Moreover, even after losing their maritime supremacy to the Europeans, whose ships were more technologically advanced, the Makassarese continued to be an active part of the South Asian seaborne trade until well developed the 19th century.

- The Makassarese visit Australia looking for sea cucumbers.

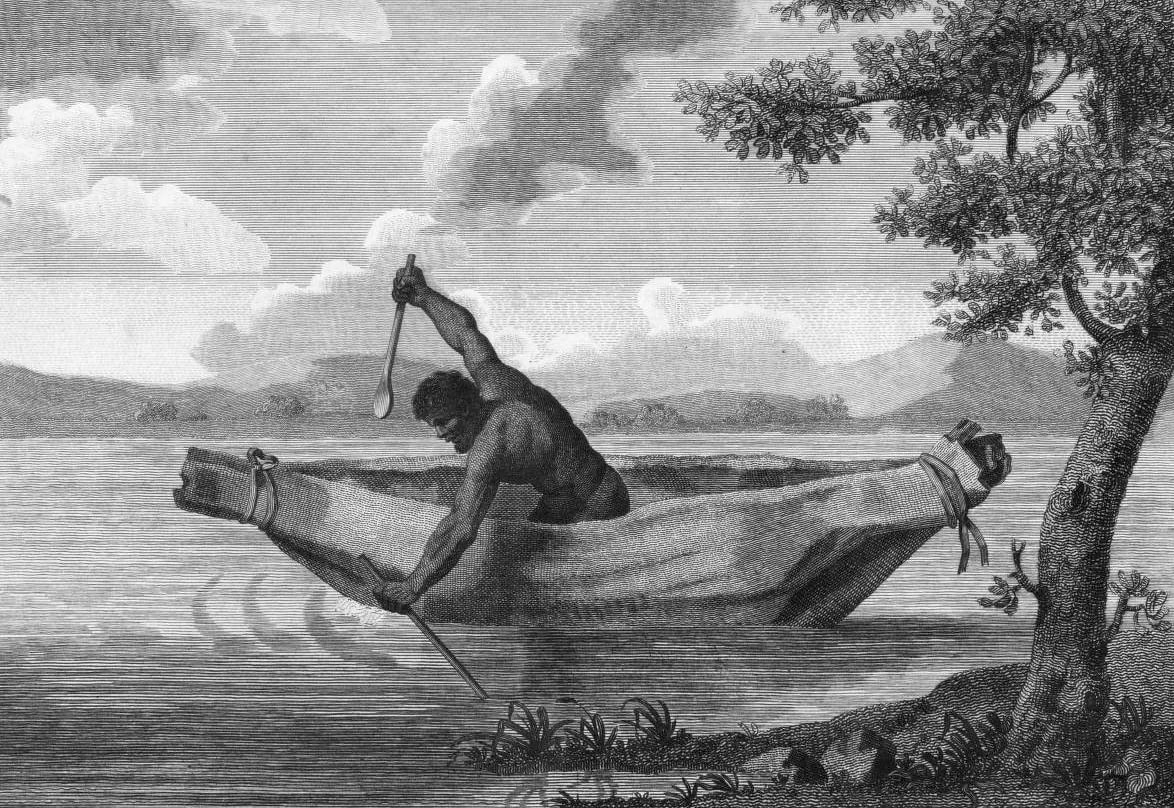

Since ancient times, the culinary value and medicine properties attributed to sea cucumbers (also known as ‘trepang’) have made these invertebrate animals a most-prized sea product in Asia.

For this reason, from about 1720 onward, fleets of Makassarese trepangers began arriving every year to the northern coasts of Australia to collect sea cucumbers that were later sold to Chinese merchants.

It must be mentioned, however, that Makassarese settlements in Australia were seasonal, which means that they didn’t settle down on the island.

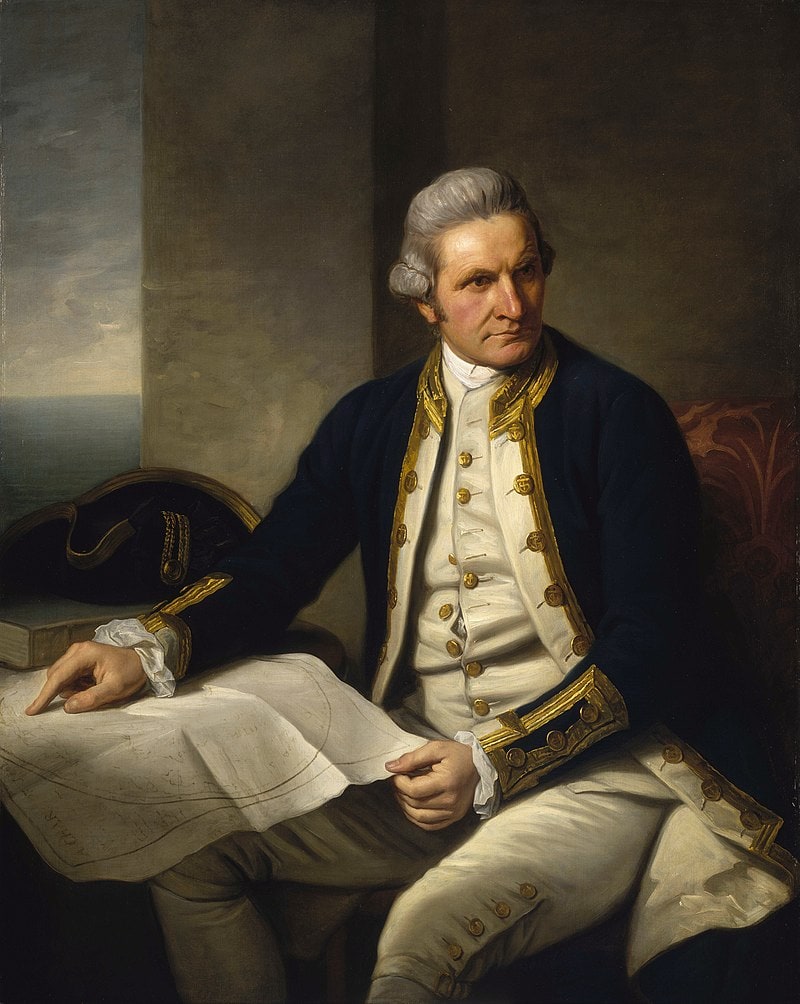

Captain Cook’s First Voyage

With the passing of time, the possibility of monopolizing the eastern sea trade motivated the British navy to continue the exploration of New Holland, where the Dutch had left it. Among the expeditions that resulted from this interest, the one led by Captain James Cook led in 1768 is of particular significance.

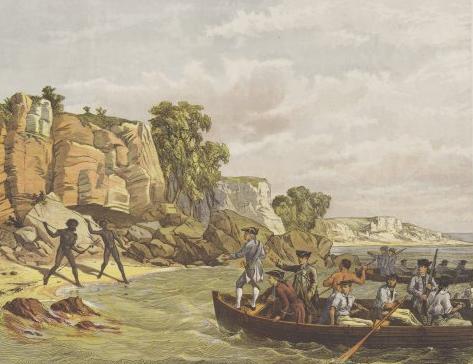

This voyage reached its turning point on April 19th, 1770, when one of the members of Cook’s crew spied the south-eastern coast of Australia.

After reaching the continent, Cook continued navigating northward across the Australian coastline. A little over a week later, the expedition found a shallow inlet, which Cook called Botany because of the variety of flora discovered there. This was the site of the first of Cook’s landings on Australian soil.

Later on, on August 23, still further to the north, Cook landed at Possession Island and claimed the land on behalf of the British empire, naming it New South Wales.

The First British Settlement in Australia

The history of the colonization of Australia began in 1786, when the British navy appointed Captain Arthur Phillip commander of an expedition that was to establish a penal colony in New South Wales. It’s worth noting that Captain Phillip was already a navy officer with a lengthy career behind him, but because the expedition was poorly funded and lacked skilled workers, the task ahead of him was daunting. Captain Phillip would demonstrate, however, that he was up to the challenge.

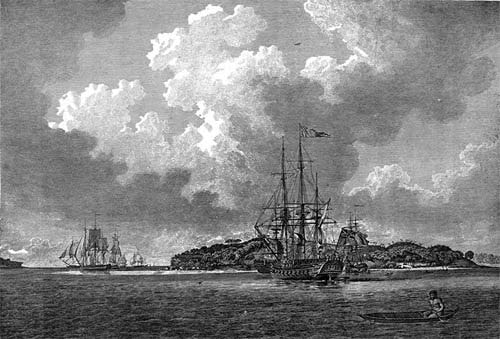

Captain Phillip’s fleet was made up of 11 British ships and about 1500 people, including convicts of both sexes, marines, and troops. They set sail from Portsmouth, England, on 17 May 1787, and reached Botany Bay, the suggested place for starting the new settlement, on 18 January 1788. However, after a brief inspection, Captain Phillip concluded that the bay was not suitable since it had poor soil and lacked a reliable source of consumable water.

The fleet kept moving northward, and on 26 January, it landed again, this time at Port Jackson. After checking that this new location presented much more favorable conditions for settling down, Captain Phillip proceeded to establish what would become known as Sydney. It’s worth mentioning that since this colony set the basis for the future Australia, January 26th became known as Australia Day. Today, there is controversy regarding the celebration of Australia Day (January 26). The Australian Aboriginals prefer to call it Invasion Day.

On 7 February 1788, Phillip’s was inaugurated as the first Governor of New South Wales, and he immediately began working on building the projected settlement. The first several years of the colony proved to be disastrous. There were no skilled farmers among the convicts that formed the main working force of the expedition, which resulted in a lack of food. However, this slowly changed, and over time, the colony grew prosperous.

In 1801, the British government assigned the English navigator Matthew Flinders with the mission of completing the charting of New Holland. This he did during the following three years and became the first known explorer to circumnavigate Australia. When he returned in 1803, Flinders prompted the British government to change the name of the island to Australia, a suggestion that was accepted.

The Decimation of Australian Aborigines

During the British colonization of Australia, long-lasting armed conflicts, known as the Australian Frontier Wars, were held between the white settlers and the aboriginal population of the island. According to traditional historical sources, at least 40,000 locals were killed between 1795 and the early 20th century due to these wars. However, more recent evidence suggests that the actual number of indigenous casualties might be closer to 750,000, with some sources even increasing the number of deaths to one million.

The first ever-recorded frontier wars fought consisted of three non-consecutive conflicts:

- Pemulwuy’s War (1795-1802)

- Tedbury’s War (1808-1809)

- Nepean War (1814-1816)

Initially, the British settlers respected their order of trying to live peacefully with the locals. However, tensions began to grow between the two parties.

Diseases brought by the Europeans, such as the smallpox virus which killed at least 70% of the indigenous population, decimated the local people who had no natural immunity against these strange ailments.

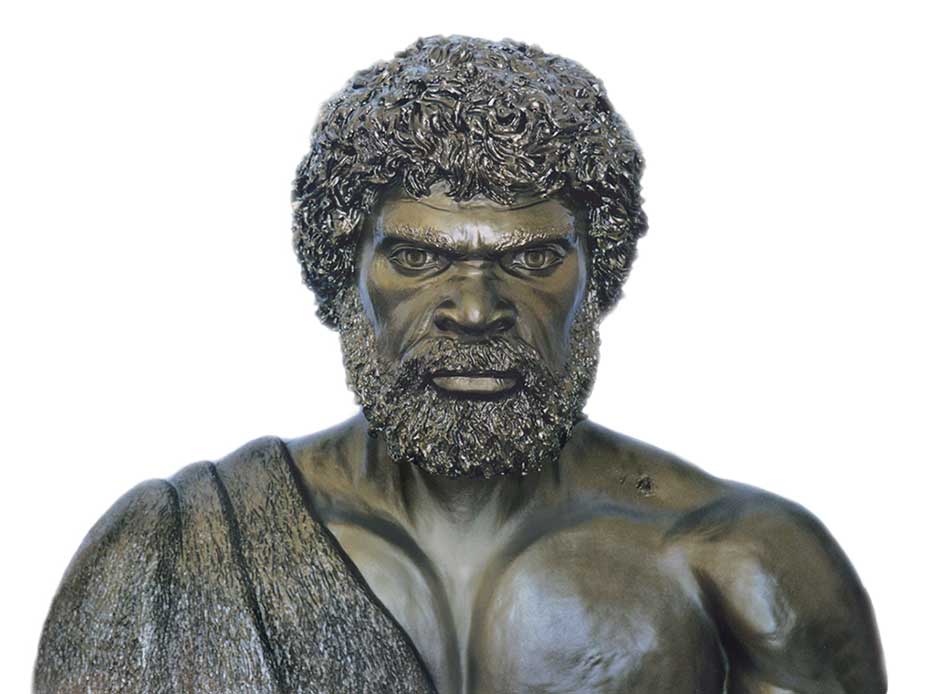

The white settlers also began invading the lands around Sydney Harbour, which traditionally belonged to the Eora people. Some Eora men then began engaging in retaliatory raids, attacking the invaders’ livestock and burning their crops. Of significant importance for this early stage of the indigenous resistance was the presence of Pemulwuy, a leader from the Bidjigal clan that led several guerrilla war-like assaults to the newcomers’ settlements.

Pemulwuy was a fierce warrior, and his actions helped to temporarily delay the colonial expansion across Eora’s lands. During this period, the most substantial confrontation in which he was involved was the Battle of Parramatta, which occurred in March 1797.

Pemulwuy attacked a government farm at Toongabbie, with a contingent of about one hundred indigenous spearmen. During the assault, Pemulwuy was shot seven times and was captured, but he recovered and eventually managed to escape from where he was imprisoned – a feat that added to his reputation as a tough and clever opponent.

It’s worth mentioning that this hero of the indigenous resistance continued to fight off the white settlers for five more years, until he was shot to death on June 2nd, 1802.

Historians have argued that these violent conflicts should be considered as genocide, rather than as wars, given the superior technology of the Europeans, who were equipped with firearms. The aborigines, on the other hand, were fighting back using nothing more than wooden clubs, spears, and shields.

In 2008 the Prime Minister of Australia, Kevin Rudd, officially apologized for all the atrocities that the white settlers had committed against the Indigenous population.

Australia Throughout the 19th Century

During the first half of the 19th century, white settlers continued colonizing new regions of Australia, and as a result of this, the colonies of Western Australia and South Australia were proclaimed respectively in 1832 and 1836. In 1825, Van Diemen’s Land (modern-day Tasmania) became an independent colony from New South Wales.

Another significant change that occurred during this period was the emergence of the wool industry, which by the 1840s became the primary source of income for the Australian economy, with more than two million kilos of wool produced each year. Australian wool would continue to be popular in the European markets throughout the second part of the century.

The rest of the colonies that constitute the states of the Australian Commonwealth would appear from the mid-19th century onward, starting with the foundation of the colony of Victoria in 1851 and continuing with Queensland in 1859.

The Australian population also began to grow dramatically after gold was discovered in east-central New South Wale in 1851. The subsequent gold rush brought several waves of immigrants to the island, with at least 2% of the population of Britain and Ireland relocating to Australia during this period. Settlers of other nationalities, such as Americans, Norwegians, Germans, and Chinese, also increased throughout the 1850s.

Mining other minerals, such as tin and copper, also became important during the 1870s. In contrast, the 1880s were the decade of silver. The proliferation of money and the rapid development of services brought by both the wool and mineral bonanza steadily stimulated the growth of the Australian population, which by 1900 had already surpassed three million people.

During the period stretching from 1860 to 1900, reformers continuously strove to provide proper primary schooling to every white settler. During these years, substantial trade union organizations also came into existence.

The Process of Becoming a Federation

Towards the end of the 19th century, both Australian intellectuals and politicians were attracted to the idea of instituting a federation, a system of government that would allow the colonies to notoriously improve their defences against any potential invader while also strengthening their internal trade. The process of becoming a federation was slow, with conventions meeting in 1891 and 1897-1898 to develop a draft constitution.

The project was given royal assent in July 1900, and then a referendum confirmed the final draft. Finally, on 1 January 1901, the passing of the constitution allowed the six British colonies of New South Wales, Victoria, Western Australia, South Australia, Queensland, and Tasmania to become one nation, under the name of the Commonwealth of Australia. Such a change meant that from this point onwards, Australia would enjoy a greater level of independence from the British government.

Australia’s Participation in World War I

In 1903, right after the consolidation of a federal government, the military units of each colony (now Australian states) were combined to create the Commonwealth Military Forces. By late 1914 the government created an all-volunteer expeditionary army, known as the Australian Imperial Force (AIF), to support Britain in its fight against the Triple Alliance.

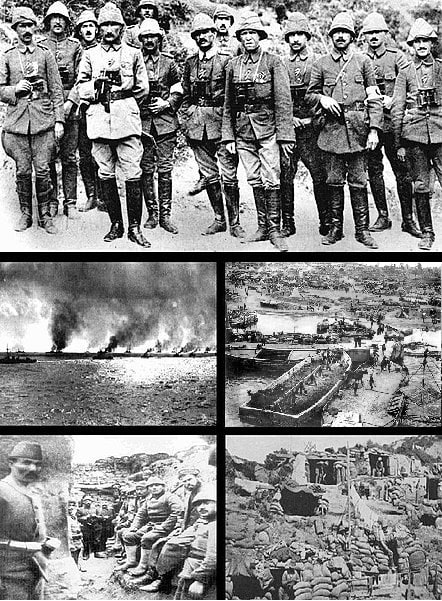

Despite not being among the principal belligerents of this conflict, Australia sent a contingent of some 330,000 men to war, most of whom fought side by side with the New Zealand forces. Known as the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC), the corps engaged in the Dardanelles Campaign (1915), where the untested ANZAC soldiers were meant to take control of the Dardanelles Strait (which at the time belonged to the Ottoman empire), in order to secure a direct supply route to Russia.

The ANZACs attack began on 25 April, the very same day of their arrival at the Gallipoli Coast. However, the Ottoman fighters presented an unexpected resistance. Finally, after several months of intense trench fighting, the Allied contingents were forced to capitulate, their forces leaving Turkey in September 1915.

At least 8,700 Australians were killed during this campaign. The sacrifice of these men is commemorated every year in Australia on 25 April on ANZAC Day.

After the defeat at Gallipoli, the ANZAC forces would be taken onto the west front, to continue fighting, this time on French territory. Approximately 60,000 Australians died and another 165,000 were wounded in the First World War. On 1 April 1921, the wartime Australian Imperial Force was disbanded.

Australia’s Participation in World War II

The toll that the Great Depression (1929) took on the Australian economy meant that the country wasn’t as prepared for the Second World War as it was for the First. Still, when Britain declared war on Nazi Germany on 3 September 1939, Australia immediately stepped into the conflict. By that time, the Citizen Military Forces (CMF) had over 80,000 men, but the CMF were legally constricted to serve only in Australia. So, on 15 September, the formation of the Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF) began.

Initially, the AIF was supposed to fight on the French front. However, after the rapid defeat of France at the hands of the Germans in 1940, part of the Australian forces was relocated to Egypt, under the name of I Corp. There, the objective of the I Corp was to prevent the Axis from gaining control over the British Suez canal, whose strategic value was of great importance for the Allies.

During the ensuing North African Campaign, the Australian forces would prove their value on several occasions, most notably at Tobruk.

In early February 1941, the German and Italian forces commanded by General Erwin Rommel (AKA the ‘Dessert Fox’) began to push eastward, chasing the Allied contingents that had previously succeeded at invading Italian Libya. The attack of Rommel’s Afrika Korps turned out to be extremely effective, and by 7 April, almost all the Allied forces had been successfully pushed back to Egypt, with the exception of a garrison placed at the town of Tobruk, formed in its majority by Australian troops.

Being closer to Egypt than any other suitable port, it was in Rommel’s best interest to capture Tobruk before continuing his march over Allied territory. However, the Australian forces positioned there effectively repulsed all Axis’s incursions and stood their ground for ten months, from 10 April to 27 November 1941, with little external support.

Throughout the Siege of Tobruk, the Australians made great use of a network of underground tunnels formerly built by the Italians, for defensive purposes. This was used by the Nazi propagandist William Joyce (AKA ‘Lord Haw-Haw’) to make fun of the besieged Allied men, who he compared to rats living in dug outs and caves. The Siege was finally held in late 1941, when an Allied coordinated operation successfully repelled the Axis forces off the port.

The relief that the Australian troops felt was brief, because they were called back home to secure the defences of the island right after the Japanese attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor (Hawaii) on December 7, 1941.

For years, Australian politicians had long feared the prospect of a Japanese invasion, and with the outbreak of the war in the Pacific, that possibility seemed more menacing now than ever. National concerns grew even further when on February 15, 1942, 15,000 Australians became war prisoners, after the Japanese forces took control of Singapore. Then, four days later, the enemy’s bombing of Darwin, a strategic Allied seaport located on the island’s North Coast, showed to the Australian government that tougher measures were required, if Japan was to be stopped.

Things get even more complicated for the Allies when the Japanese succeeded in capturing both the Dutch East Indies and the Philippines (which was US territory at the time) by May 1942. By now, the next logical step for Japan was trying to take control over Port Moresby, a strategic naval emplacement located in Papua New Guinea, something that would allow the Japanese to isolate Australia from the U.S. naval bases scattered across the Pacific, thus making it easier for them to defeat the Australian forces.

During the subsequent Battles of the Coral Sea (4-8 May) and Midway (4-7 June), the Japanese navy were almost completely crushed, making any plan for a naval incursion to capture Port Moresby no longer an option. This series of setbacks led Japan to try to reach Port Moresby overland, an attempt that would eventually start the Kokoda Track campaign.

The Australian forces put up a strong resistance against the advances of a better-equipped Japanese contingent, while at the same time facing the difficult conditions of the climate and terrain of the Papuan jungle. It’s also worth noticing that the Australian units that fought in the Kokoda track were arguably smaller than those of the enemy. This campaign lasted from 21 July to 16 November 1942. The victory at Kokoda contributed to the creation of the so-called ANZAC legend, a tradition that exalts the notable endurance of the Australian troops and still constitutes an important element of the Australian identity.

In early 1943, an act was passed to authorize the service of the Citizen Military Forces in the Southwestern Pacific zone, which implied an extension of Australia’s line of defence to the overseas territories of south-eastern New Guinea and other islands nearby. Defensive measures such as the latter significantly contributed to keeping the Japanese at bay during the rest of the war.

Close to 30,000 Australians died fighting during the Second World War.

Post-war Period and Late 20th Century

After the Second World War, the Australian economy kept growing vigorously until the early 1970s, when this expansion began to slow down.

Regarding social affairs, Australia’s immigration policies were adapted to receive a considerable number of immigrants that came mainly from the devastated post-war Europe. Another significant change came in 1967, when Australian aborigines were finally granted the status of citizens.

From the mid-1950s onward, and all throughout the sixties, the arrival of North American rock and roll music and films also vastly influenced Australian culture.

The seventies were also an important decade for multiculturalism. During this period, the White Australia policy, which had functioned since 1901, was finally abolished by the government. This allowed the influx of Asian immigrants, such as the Vietnamese, who began coming to the country in 1978.

The Royal Commission of Human Relationships, created in 1974, also contributed to promulgating the need of discussing the rights of women and the LGBTQ community. This commission was dismantled in 1977, but its work set an important antecedent, as it’s considered as part of the process that led to the decriminalization of homosexuality in all the Australian territories in 1994.

Another major change took place in 1986, when political pressure led the British Parliament to pass the Australia Act, which formally made it impossible for Australian courts to appeal to London. In practice, this enactment meant that Australia had finally become a fully independent nation.

In Conclusion

Today Australia is a multicultural country, popular as a destination for tourists, international students, and immigrants. An ancient land, it’s known for its beautiful natural landscapes, warm and friendly culture, and having some of the world’s most deadly animals.

Carolyn McDowall says it best in the Culture Concept when she says, “Australia is a country of paradoxes. Here birds laugh, mammals lay eggs and raise babies in pouches and pools. Here everything may seem familiar yet, somehow, it’s not really what you are used to.”