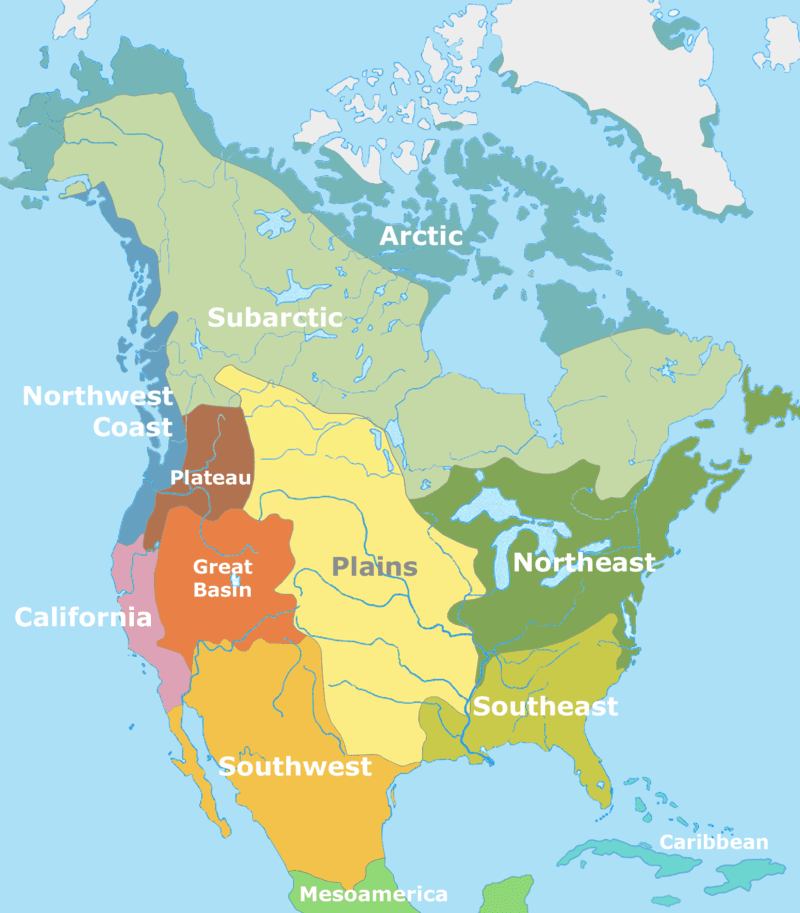

Given the vast size of North America, describing how Native American art has evolved is anything but an easy task. However, art historians have discovered that there are five major regions, in this territory, that have indigenous artistic traditions with characteristics that are unique to these peoples and places.

Today we’ll be discussing how Native American art has manifested in each one of these five areas.

Is the Art of Every Native American Group the Same?

No. Similar to what happens in the southern and central parts of the continent, there is no such thing as a pan-Indian culture in North America. Even long before the arrival of the Europeans to these territories, the tribes that lived here were already practicing different kinds of art forms.

How Did the Native Americans Traditionally Conceive Art?

In the traditional Native American perception, the artistic value of an object is determined not only by its beauty but also by how ‘well-done’ the artwork is. This doesn’t mean that Native Americans were incapable of valuing the beauty of things, but rather that their appreciation of art was primarily based on quality.

Other criteria for deciding if something is artistic or not might be if the object could properly fulfill the practical function for which it was created, who has owned it before, and how many times the object has been used in a religious ceremony.

Finally, to be artistic, an object also had to represent, in one way or another, the values of the society from which it came. This often implied that the indigenous artist was only able to use only a predetermined set of materials or processes, something that could limit his or her freedom of creation.

However, there are known cases of individuals who reinvented the artistic tradition to which they belonged; this is the case, for instance, of the Puebloan artist María Martinez.

The First Native American Artists

The first Native American artists walked on Earth way back in time, sometime around 11000 BCE. We don’t know much about the artistic sensibility of these men, but one thing is for sure – survival was one of the main things that were on their minds. This can be corroborated by observing which elements drew the attention of these artists.

For instance, from this period we find a Megafauna bone with the image of a walking mammoth etched on it. It’s known that ancient men hunted down mammoths for several millennia, as these animals represented a significant source of food, clothing, and shelter for them.

Five Major Regions

While studying the evolution of Native American art, historians have discovered that there are five major regions in this part of the continent that present their own artistic traditions. These regions are the Southwest, the East, the West, the Northwest Coast, and the North.

The five regions within North America present artistic traditions that are unique to the indigenous groups that live there. Briefly, these are as follows:

- Southwest: Pueblo people specialized in the creation of fine domestic utensils such as clay vessels and baskets.

- East: The indigenous societies from the Great Plains developed large mound complexes, to be the burial place of the members of the high classes.

- West: More interested in the social functions of art, the Native Americans from the West used to paint historical accounts on buffalo hides.

- Northwest: The aborigines from the Northwest Coast preferred to carve their history on totems.

- North: Finally, the art from the North seems to be the most influenced by religious thought, as the artworks from this artistic tradition are created to show respect to the animal spirits of the Arctic.

Southwest

The Pueblo people are a Native American group located primarily in the northeastern part of Arizona and New Mexico. These aborigines descend from the Anasazi, an ancient culture that reached its peak between 700 BCE and 1200 BCE.

Representative of Southwest art, Pueblo people have done fine pottery and basketry for many centuries, perfecting particular techniques and decorating styles that show a taste for both simplicity and motifs inspired by North American nature. Geometric designs are also popular among these artists.

Techniques of pottery production might vary from one locality to another in the Southwest. However, what is common in all cases is the complexity of the process regarding the preparation of the clay. Traditionally, only Pueblo women could harvest the clay from the Earth. But the role of Pueblo women is not limited to this, as for centuries one generation of female potters has passed down to the other the secrets of pottery making.

Choosing the type of clay they are going to work with is just the first of many steps. After that, potters must purify the clay, as well as select the specific tempering they would be using in their mixture. For most potters, prayers precede the stage of kneading the pot. Once the vessel is molded, Pueblo artists proceed to light a fire (which is commonly placed on the ground), for firing the pot. This also requires a profound knowledge of the resistance of the clay, its shrinkage, and the force of the wind. The last two steps consist of the polishing and decorating of the pot.

Maria Martinez of San Ildefonso Pueblo (1887-1980) is perhaps the most famous of all Pueblo artists. The pottery work Maria became notorious due to her combining ancient traditional techniques of pottering with stylistic innovations brought by her. The experimentation with the firing process and the use of black-and-black designs characterized Maria’s artistic work. Initially, Julian Martinez, María’s husband, decorated her pots until he died in 1943. She then continued the work.

East

The term Woodland people is used by historians to designate the group of Native Americans that lived on the eastern part of the continent.

Although indigenous from this area are still producing art, the most impressive artwork created here belongs to the ancient Native American civilizations that flourished between the late Archaic Period (close to 1000 BCE) and the middle-Woodland period (500 CE).

During this time, Woodland people, particularly the ones that came from the Hopewell and Adena cultures (both located in southern Ohio), specialized in the construction of large-scale mound complexes. These mounds were highly artistically decorated, as they served as burial sites dedicated to members of the elite classes or notorious warriors.

Woodland artists would often work with fine materials such as copper from the Great Lakes, lead ore from Missouri, and different kinds of exotic stones, to create exquisite jewelry, vessels, bowls, and effigies that were supposed to accompany the dead in their mounts.

While both the Hopewell and the Adena cultures were great mound-builders, the latter also developed a superior taste for stone carved pipes, traditionally used in healing and political ceremonies, and stone tablets, which might have been used for wall decoration.

By the year 500 CE, these societies had disintegrated. However, much of their belief systems and other cultural elements were eventually inherited by the Iroquois peoples.

These newer groups didn’t have the manpower nor the luxury necessary to continue with the tradition of the mount building, but they still practiced other inherited art forms. For instance, wood carving has allowed the Iroquois to reconnect with their ancestral origins–especially after they were dispossessed of their lands by European settlers during the post-contact period.

West

During the post-contact period, the land of the North American Great Plains, in the west, was inhabited by more than two dozen different ethnic groups, among them the Plains Cree, Pawnee, Crow, Arapaho, Mandan, Kiowa, Cheyenne, and Assiniboine. Most of these people led a nomadic or semi-nomadic lifestyle that was defined by the presence of the buffalo.

Up until the second half of the 19th century, the buffalo provided most Great Plains’ Native Americans with food as well as with elements necessary for producing clothing and building shelters. Moreover, talking about the art of these people is virtually impossible without considering the importance that the buffalo hide had for the artists of the Great Plains.

Buffalo hide was artistically worked by both Native American men and women. In the first case, men used buffalo hides to paint historical accounts over them and also to create shields that were imbued with magical properties, to ensure physical and spiritual protection. In the second case, women would work collectively to produce large tipis (typical Native American tends), decorated with beautiful abstract designs.

It’s worth mentioning that the stereotype of the ‘common Native American’ promoted by most of the westernized media is based on the look of the indigenous from the Great Plains. This has led to many misconceptions, but one that specifically attained to these peoples is the belief that their art is exclusively centered on war prowess.

This kind of approach jeopardizes the possibility of having an accurate understanding of one of the richest Native American artistic traditions.

North

In the Arctic and the Sub-Arctic, the indigenous population has engaged in the practice of different art forms, being perhaps the creation of preciously decorated hunter clothing and hunting equipment the most delicate of all.

Since ancient times, religion has permeated the lives of the Native Americans that inhabit the Arctic, an influence that is also palpable in the other two principal art forms practiced by these people: the carving of amulets and the creation of ritual masks.

Traditionally, animism (the belief that all animals, humans, plants, and objects have a soul) has been the fundament of the religions practiced by the Inuits and the Aleuts-two groups that constitute the majority of the indigenous population in the Arctic. Coming from hunting cultures, these peoples believe that it’s important to appease and keep good relationships with the animal spirits, so they would continue to cooperate with humans, thus making hunting possible.

One way in which Inuit and Aleut hunters traditionally show their respect for these spirits is by wearing clothing embellished with fine animal designs. At least until the mid-19th century, it was a common belief among the Arctic tribes that animals preferred to be killed by hunters that wore decorated attires. Hunters also thought that by incorporating animal motifs into their hunting garments, the powers and protection of the animal spirits would be transferred to them.

During the long Arctic nights, indigenous women would spend their time creating visually appealing clothing and hunting utensils. But these artists showed creativity not only when developing their beautiful designs, but also at the moment of choosing their working materials. Arctic craftswomen would traditionally use a wide variety of animal materials, ranging from deer, caribou, and hare hide, to salmon skin, walrus intestine, bone, antlers, and ivory.

These artists also worked with vegetal materials, such as bark, wood, and roots. Some groups, like the Crees (an indigenous people that live primarily in Northern Canada), also used mineral pigments, up until the 19th century, to produce their palettes.

Northwest Coast

North America’s Northwest Coast extends from the Copper River in Southern Alaska to the Oregon–California border. The indigenous artistic traditions from this region have a long-time depth, as they began approximately around the year 3500 BCE, and have continued evolving almost uninterruptedly in the majority of this territory.

Archeological evidence shows that by 1500 BCE, many Native American groups from all around this area had already mastered art forms such as basketry, weaving, and wood carving. However, despite having initially shown great interest in creating small delicately carved effigies, figurines, bowls, and plates, the attention of these artists turned in time to the production of the large totem poles for which the Northwest Coast is so well-known.

To understand why this change took place, it’s necessary to know first that the Native American societies that developed on the Northwest Coast had established very well-defined systems of classes. Moreover, families and individuals that were on the top of the social ladder would continuously look for artists who could create visually impressive artworks that served as a symbol of their wealth and power. This is also why totem poles were commonly displayed in front of the houses belonging to those who paid for them.

Totem poles were usually made of cedar logs and could be as high as 60 feet long. They were carved with a technique known as formline art, which consists of carving asymmetrical shapes (ovoids, U forms, and S forms) onto the surface of the log. Each totem is decorated with a set of symbols that represent the history of the family or the person that owns it. It’s worth noting that the idea that totems should be adored is a common misconception spread by non-indigenous people.

The social function of totems, as providers of historical accounts, is best observed during the celebration of potlatches. Potlatches are great feasts, traditionally celebrated by Northwest Coast Native people, where the power of certain families or individuals is publicly acknowledged.

Moreover, according to the art historians Janet C. Berlo and Ruth B. Phillips, it’s during these ceremonies that the stories presented by the totems “explain, validate, and reify the traditional social order”.

Conclusion

Among the Native American cultures, the appreciation of art was based on quality, rather than on aesthetic aspects. Native American art is also characterized by its practical nature, as much of the artwork created in this part of the world was thought to be used as utensils for common daily activities or even in religious ceremonies.