Table of Contents

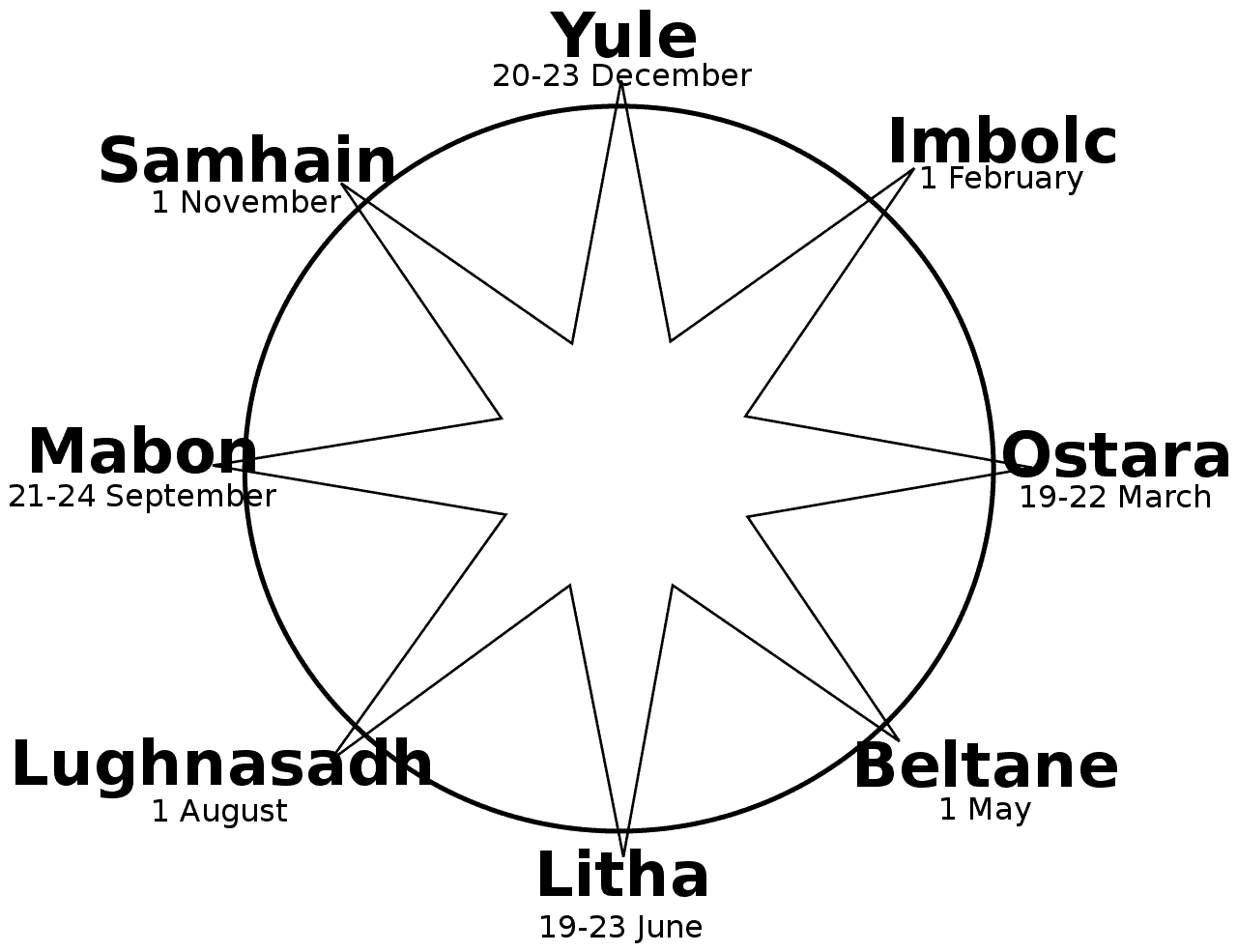

The Celts had great respect for the changing of season, honoring the sun as it passed through the heavens. Along with the solstices and equinoxes, the Celts also marked the cross-quarter days sitting between major seasonal shifts. Lammas is one of these, along with Beltane (May 1st), Samhain (November 1st) and Imbolc (February 1st).

Also known as Lughassadh or Lughnasad (pronounced lew-na-sah), Lammas falls between the Summer Solstice (Litha, June 21st) and the Fall Equinox (Mabon, September 21st). This is the first grain harvest of the season for wheat, barley, corn, and other produce. This holiday is still celebrated today among modern pagans. Let’s take a look at the rituals, symbols, and importance of Lammas.

Importance of Lammas – The First Harvest

Grain was an incredibly important crop to many ancient civilizations and the Celts were no exception. In the weeks before Lammas, the risk of starvation was at its highest as the stores kept for the year became dangerously close to depletion.

If the grain stayed too long in the fields, was taken in too early, or if people didn’t produce baked goods, starvation became a reality. Unfortunately, the Celts saw these as signs of agricultural failure in providing for the community. Performing rituals during Lammas helped to guard against this failure.

Therefore, the most important activity of Lammas was cutting the first sheaves of wheat and grain early in the morning. By nightfall, the first loaves of bread were ready for the communal feast.

What Do People Do At Lammas?

Lammas heralded a return to plenty with rituals reflecting the need for protecting food and livestock. This festival also marked the end of summer and bringing in the cattle set out to pasture during Beltane.

People would use this time to terminate or renew contracts. This included marriage proposals, servant hiring/firing, trade, and other forms of business. They presented gifts to each other as an act of genuine sincerity and contractual agreement.

Although Lammas was generally the same throughout the Celtic world, various areas practiced different customs. Most of what we know about these traditions comes from Scotland.

Lammastide in Scotland

“Lammastide,” “Lùnastal” or “Gule of August” was an 11-day harvest fair, and the role of women was tantamount. The largest of these was at Kirkwall in Orkney. For centuries, such fairs were something to behold and covered the entire country, but by the end of the 20th century, only two of these remained: St. Andrews and Inverkeithing. Both still have Lammas Fairs today complete with market stalls, food, and drink.

1. Trial Weddings

Lammastide was the time for performing trial weddings. This allowed couples to live together for a year and a day. If the match wasn’t desirable, there was no expectation of staying together. They would “tie a knot” of colored ribbons and women wore blue dresses to formalize the arrangement. If all went well, they would be married the following year.

2. Decorating Livestock

Women blessed cattle to keep evil away for the next three months, a ritual called “saining.” They would put tar along with blue and red threads on the animals’ tails and ears. They also hung charms from udders and necks. The decorations accompanied several prayers, rituals, and incantations. Although we know the women did this, what the exact words and rites were is lost to time.

3. Food and Water

Another ritual was the milking of cows by women early in the morning. This collection was put into two portions. One would have a ball of hair in it to keep the contents strong and good. The other was allocated to the making of small cheese curds for children to eat with the belief it would bring them luck and goodwill.

To protect byres and homes from harm and evil, specially prepared water was placed around door posts. A piece of metal, sometimes a woman’s ring, would steep in the water before sprinkling it around.

4. Games and Processions

Edinburgh farmers engaged in a game in which they would build a tower for competing communities to knock down. They, in turn, would try to knock down their opponent’s towers. This was a boisterous and dangerous contest that frequently ended in death or injury.

In Queensferry, they undertook a ritual called the Burryman. The Burryman walks through the town, crowned with roses and a staff in each hand along with a Scottish flag tied around the midsection. Two “officials” would accompany this man along with a bellringer and chanting children. This procession collected money as an act of luck.

Lughnasad in Ireland

In Ireland, Lammas was known as “Lughnasad” or “Lúnasa”. The Irish believed harvesting grain before Lammas was bad luck. During Lughnasad, they too practiced marriage and love tokens. Men offered baskets of blueberries to a love interest and still do this today.

Christian Influences on Lammas

The word “Lammas” comes from the old English “haf maesse” that translates loosely to “loaf mass”. Therefore, Lammas is a Christian adaptation of the original Celtic festival and represents the efforts of the Christian church to suppress the pagan Lughnasad traditions.

Today, Lammas is celebrated as Loaf Mass Day, a Christian holiday on 1st of August. It references the main Christian liturgy which celebrates the Holy Communion. In the Christian year, or liturgical calendar, it marks the blessings of the First Fruits of the harvest.

However, neopagans, Wiccans and others continue to celebrate the original pagan version of the festival.

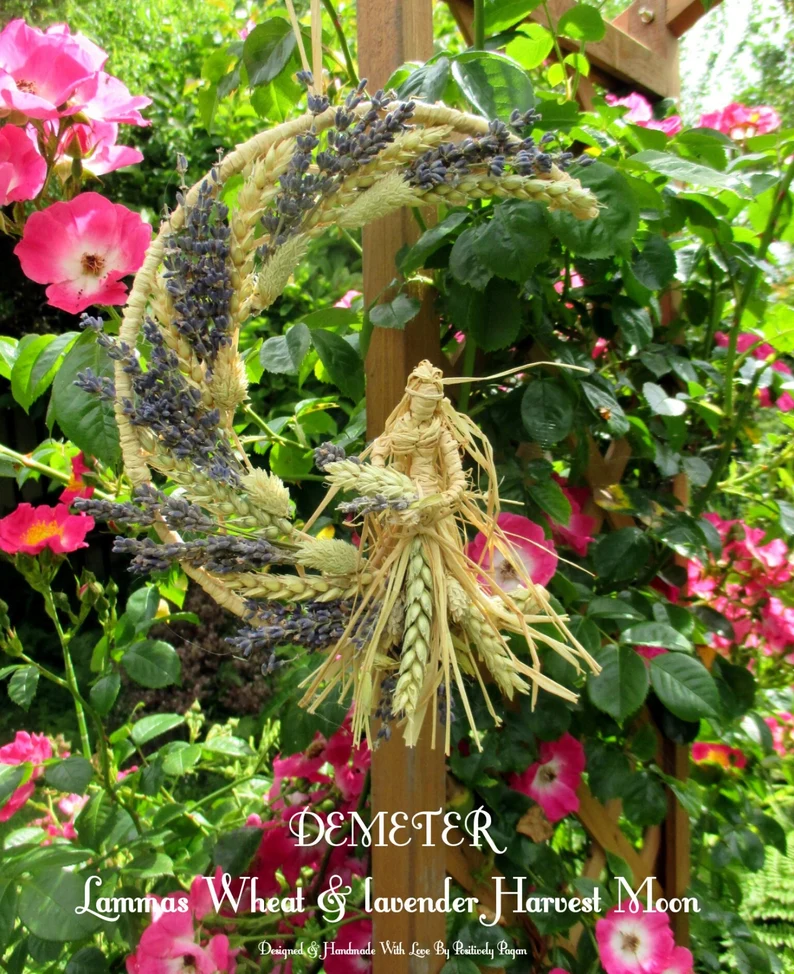

Today’s celebrations of Lammas/Lughnasad continue to include bread and cakes along with altar decorations. These include symbols like scythes (for cutting grain), corn, grapes, apples, and other seasonal foods.

Symbols of Lammas

As Lammas is all about celebrating the start of the harvest, the symbols associated with the festival are related to the harvest and the time of the year. Symbols of Lammas include:

- Grains

- Flowers, especially sunflowers

- Leaves and herbs

- Bread

- Fruits that represent the harvest, such as apples

- Spears

- The deity Lugh

These symbols can be placed on the Lammas altar, which is usually created to face west, the direction associated with the season. Of these, the loaf of bread is one of the most important as it represents how grain can be transformed into nourishment, much like the growth cycles of nature. Often, the first loaf baked from the new crop would be blessed and used in rituals.

Lugh – The Deity of Lammas

Most Lammas celebrations honor the savior and trickster god, Lugh (pronounced LOO). This is where the name Lughnasad comes from. In Wales, he was called Llew Law Gyffes and on the Isle of Mann they called him Lug. He is the god of crafts, judgment, blacksmithing, carpentry and fighting along with trickery, cunning and poetry.

Some say the celebration of August 1st is the date of Lugh’s wedding feast and others contest it was in honor of his foster mother, Tailtiu, who passed away from exhaustion after clearing the lands for planting crops throughout Ireland.

According to Celtic mythology, upon conquering the spirits who dwell in Tír na nÓg (the Celtic Otherworld translating to “Land of the Young”), Lugh commemorated his victory with Lammas. The early fruits of harvest and competitive games were in remembrance of Tailtiu.

Why Is Lugh Associated with Lammas?

The name Lugh itself could be from the Proto-Indo-European root word “lewgh” which means to bind by oath. This makes sense regarding his role in oaths, contracts, and wedding vows. Some people believe Lugh’s name is synonymous with light, but most scholars don’t subscribe to this.

Although he isn’t the personification of light, Lugh has a definite connection to it through the sun and fire. We can gain better context by comparing his festival to other cross quarter festivals.

On February 1st the focus is around the goddess Brigid’s protective fire and the growing days of light into summer. But during Lammas, the attention is on Lugh as a destructive agent of fire and the representative of summer’s end. This cycle comes to completion and restarts during Samhain on November 1st.

Lugh’s name could also mean “artful hands”, which references poetry and craftsmanship. He can create beautiful, unparalleled works but he is also the epitome of force. His ability to manipulate weather, bring storms, and throw lightning with his spear highlights this ability.

More affectionately referred to as “Lámfada” or “Lugh of the Long Arm”, he is a great battle strategist and decides war victories. These judgments are final and unbreakable. Here, Lugh’s warrior attributes are clear – smashing, attacking, fierceness and aggression. This would explain the many athletic games and fighting competitions during Lammas.

How Is Lammas Celebrated Today?

Today, Lammas remains a popular pagan festival. How it’s celebrated depends on the various cultural practices and pagan contexts. Wiccan and other Neopagan communities often hold ceremonies to honor their deities, like Demeter or Lugh. They also engage in symbolic activities like making corn husk dolls Lammas loaves, bread in the shape of a man or the sun to represent the spirit of the grain.

Lammas continues to appeal to people today, especially those who seek to reconnect with nature and the cycle of the seasons. It’s also a celebration of food, family, and community – things that appeal to everyone universally.

In Brief

Lammas is a time of plenty with Lugh’s arrival signaling the beginning of the end of summer. It’s a time of celebrating the efforts that went into the harvest. Lammas ties together the seed planting from Imbolc and propagation during Beltane. This culminates with the promise of Samhain, where the cycle starts over again.