Table of Contents

Bushido was established around the eighth century as a code of conduct for the samurai class of Japan. It was concerned with the behavior, lifestyle, and attitudes of the samurai, and detailed guidelines for a principled life.

The principles of Bushido continued to exist even after the abolishment of the samurai class in 1868, becoming a fundamental aspect of Japanese culture.

What is Bushido?

Bushido, literally translating to Warrior way, was first coined as a term in the early 17th century, in the 1616 military chronicle Kōyō Gunkan. Similar terms used at the time included Mononofu no michi, Samuraidô, Bushi no michi, Shidô, Bushi katagi, and many others.

In fact, several similar terms predate Bushido as well. Japan had been a warrior culture for centuries before the start of the Edo period at the beginning of the 17th century. Not all of those were exactly like Bushido, however, nor did they serve the exact same function.

Bushido in the Edo Period

So, what changed in the 17th century to make Bushido stand out from other warrior codes of conduct? In a few words – the unification of Japan.

Before the Edo period, Japan had spent centuries as a collection of warring feudal states, each ruled by its respective daimyo feudal lord. In the late 16th century and early 17thh century, however, a major conquest campaign was started by the daimyo Oda Nobunaga, which was then continued by his successor and former samurai Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and was finalized by his son Toyotomi Hideyori.

And the result of this decades-long campaign? A unified Japan. And with that – peace.

So, while for centuries previously the job of the samurai was almost exclusively to wage war, during the Edo period their job description started to change. The samurai, still warriors and servants to their daimyos (themselves now under the rule of Japan’s military dictators, known as shogun) had to live in peace more often than not. This meant more time for social events, for writing and art, for family life, and more.

With these new realities in the lives of the samurai, a new moral code had to emerge. That was Bushido.

No longer just a code of military discipline, courage, valor, and sacrifice in battle, Bushido also served civic purposes. This new code of conduct was used to teach the samurai how to dress in specific civic situations, how to welcome higher-up guests, how to better police the peace in their community, how to behave with their families, and so on.

Of course, Bushido was still a warrior’s code of conduct. A large part of it was still about the samurai’s duties in battle and his duties to his daimyo, including the duty to commit seppuku (a form of ritual suicide, also called hara-kiri) in case of failure to protect the samurai’s master.

However, as the years passed, an increasing number of non-military codes were added to Bushido, making it an overarching everyday code of conduct and not just a military code.

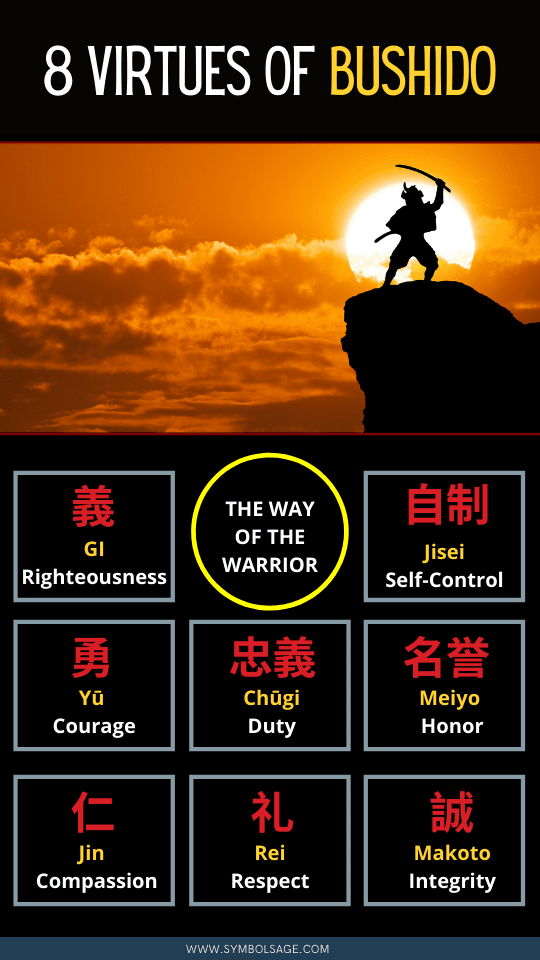

What Are the Eight Principles of Bushido?

The Bushido code contained eight virtues or principles that its followers were expected to observe in their daily life. These are:

1- Gi – Justice

A fundamental tenet of the Bushido code, you should be just and honest in all your interactions with others. Warriors should reflect on what is true and just and be righteous in all they do.

2- Yū – Courage

Those are note courageous, do not live at all. To live a courageous life is to live fully. A warrior should be courageous and fearless, but this should be tempered with intelligence, reflection, and strength.

3- Jin – Compassion

A true warrior should be strong and powerful, but they should also be empathetic, compassionate, and sympathetic. To have compassion, it’s necessary to be respectful of and acknowledge the perspectives of others.

4- Rei – Respect

A true warrior should be respectful in their interactions with others and should not feel the need to flaunt their strength and power over others. Respecting the feelings and experiences of others and being polite when dealing with them is essential for successful collaboration.

5- Makoto – Integrity

You should stand by what you say. Do not speak empty words – when you say you will do something, it should be as good as done. By living honestly and with sincerity, you will be able to keep your integrity intact.

6- Meiyo – Honor

A true warrior will act honorably not for fear of the judgement of others, but for themselves. The decisions they make and the acts that they carry out should align with their values and their word. This is how honor is safeguarded.

7- Chūgi – Duty

A warrior must be loyal to those they are responsible for and have a duty to protect. It’s important to follow through on what you say you will do and to be responsible for the consequences of your actions.

8- Jisei – Self-Control

Self-control is an important virtue of the Bushido code and is required in order to properly follow the code. It’s not easy to always do what is right and moral, but by having self-control and discipline, one will be able to walk the path of a true warrior.

Other Codes Similar to Bushido

As we mentioned above, Bushido is far from being the first moral code for samurai and military men in Japan. Bushido-like codes from the Heian, Kamakura, Muromachi, and Sengoku Periods had existed.

Ever since the Heian and Kamakura periods (794 AD to 1333) when Japan started becoming increasingly militaristic, different written moral codes started to emerge.

This was largely necessitated by the samurai overthrowing the ruling Emperor in the 12th century and replacing him with a shogun – formerly the military deputy of the Japanese Emperor. Essentially, the samurai (also called bushi at the time) performed a military junta.

This new reality led to a change in the samurai’s status and role in society, hence the new and emerging codes of conduct. Still, these largely revolved around the samurai’s military duties to their new hierarchy – the local daimyo lords and the shogun.

Such codes included Tsuwamon no michi (Way of the man-at-arms), Kyûsen / kyûya no michi (Way of the bow and arrows), Kyūba no michi (Way of the bow and the horse), and others.

All these largely focused on the various styles of combat employed by samurai in different areas of Japan as well as different time periods. It’s easy to forget that samurai were just swordfighters – in fact, they mostly used bows and arrows, fought with spears, rode horses, and even used fighting staves.

The different predecessors of Bushido focused on such military styles as well as on overall military strategy. Still, they also focused on the morality of war too – the valor and honor that was expected of the samurai, their duty to their daimyo and shogun, and so on.

For example, the ritual seppuku (or harakiri) self-sacrifices that samurai were expected to do if they lost their master or were disgraced is often associated with Bushido. However, the practice was in place centuries before the invention of Bushido in 1616. In fact, as early as the 1400s, it had even become a common type of capital punishment.

So, while Bushido is unique in many ways and in how it encompasses a wide range of morals and practices, it’s not the first moral code the samurai were expected to follow.

Bushido Today

After the Meiji Restoration, the samurai class was done away with, and the modern Japanese conscript army was established. However, the Bushido code continues to exist. The virtues of the samurai warrior class can be found in Japanese society, and the code is considered a significant aspect of Japanese culture and lifestyle.

Japan’s image as a martial country is the legacy of the samurai and the principles of Bushido. As Misha Ketchell writes in The Conversation, “The imperial bushido ideology was used to indoctrinate the Japanese servicemen who invaded China in the 1930s and attacked Pearl Harbour in 1941.” It’s this ideology that resulted in the no surrender image of the Japanese military during World War II. After World War II and as with many ideologies of the time, Bushido also was viewed as a dangerous system of thought and was largely rejected.

Bushido experienced a revival in the second half of the 20th century and continues today. This Bushido rejects the military aspects of the code, and instead stresses the virtues required for a good life – including honesty, discipline, compassion, empathy, loyalty, and virtue.

FAQs About Bushido

If a warrior felt that they had lost their honor, they could salvage the situation by committing seppuku – a form of ritual suicide. This would give them back the honor they had lost or were about to lose. Ironically, they wouldn’t be able to witness let alone enjoy that.

There are seven official virtues, with the eight unofficial virtue being self-control. This last virtue was required in order to apply the rest of the virtues and ensure that they were put into action effectively.

Bushido was established in Japan and was practiced in several other Asian countries. In Europe, the chivalric code followed by the Medieval knights was somewhat similar to the Bushido code.

Wrapping Up

As a code for a principled life, Bushido offers something for everyone. It stresses the importance of being true to your word, accountable for your actions, and loyal to those who depend on you. While its military elements are largely rejected today, Bushido is still an essential aspect of the fabric of Japanese culture.