The Women’s Rights Movement is one of the most influential social movements of the past two centuries in the Western world. In terms of its social impact it only really compares to the Civil Rights Movement and – more recently – to the movement for LGBTQ rights.

So, what exactly is the Women’s Rights Movement and what are its goals? When did it officially start and what is it fighting for today?

The Beginning of the Women’s Rights Movement

The start date of the Women’s Rights Movement is accepted as the week of the 13th to 20th of July, 1848. It was during this week, in Seneca Falls, New York, that Elizabeth Cady Stanton organized and held the first convention for women’s rights. She and her compatriots named it “A convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of women.”

While individual women’s rights activists, feminists, and suffragettes had been talking and writing books about women’s rights before 1848, this was when the Movement officially began. Stanton further marked the occasion by writing her famous Declaration of Sentiments, modeled on the US Declaration of Independence. The two pieces of literature are rather similar with some clear differences. For example, Stanton’s Declaration reads:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

The Declaration of Sentiments further goes to outlines areas and walks of life where women were treated unequally, such as work, the electoral process, marriage and the household, education, religious rights, and so on. Stanton summed all these grievances in a list of resolutions written in the Declaration:

- Married women were legally seen as mere property in the eyes of the law.

- Women were disenfranchised and didn’t have the right to vote.

- Women were forced to live under laws they had no voice in creating.

- As “property” of their husbands, married women were unable to have any property of their own.

- The legal rights of the husband extended so far over his wife whom he could even beat, abuse, and imprison if he so chose.

- Men had complete favoritism in regards to child custody after divorce.

- Unmarried women were allowed to own property but had no say in the formation and extent of the property taxes and laws they had to pay and obey.

- Women were restricted from most occupations and were grossly underpaid in the few professions they had access to.

- Two main professional areas women were not allowed into included law and medicine.

- Colleges and universities were closed for women, denying them the right to higher education.

- Women’s role in the church was also severely restricted.

- Women were made completely dependent on men which was devastating for their self-respect and confidence, as well as their public perception.

Funnily enough, while all of these grievances were passed at the Seneca Falls convention, only one of them wasn’t unanimous – the resolution about women’s right to vote. The whole concept was so foreign for women at the time that even many of the staunchest feminists at the time didn’t see it as possible.

Still, the women at the Seneca Falls convention were determined to create something significant and long-lasting, and they knew the full scope of the problems they faced. That much is evident from another famous quote from the Declaration that states:

“The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her.”

The Backlash

In her Declaration of Sentiments, Stanton also talked about the backlash the Women’s Rights movement was about to experience once they started working.

She said:

“In entering upon the great work before us, we anticipate no small amount of misconception, misrepresentation, and ridicule; but we shall use every instrumentality within our power to effect our object. We shall employ agents, circulate tracts, petition the State and national Legislatures, and endeavor to enlist the pulpit and the press on our behalf. We hope this Convention will be followed by a series of Conventions, embracing every part of the country.”

She was not wrong. Everyone, from politicians, the business class, the media, to the middle-class man were outraged by Stanton’s Declaration and the Movement she had started. The resolution that sparked the most ire was the same one that even the suffragettes themselves didn’t unanimously agree was possible – that of the women’s right to vote. Newspaper editors across the US and abroad were outraged by this “ludicrous” demand.

The backlash in the media and the public sphere was so severe, and the names of all the participants were exposed and ridiculed so shamelessly, that many of the participants in the Seneca Falls Convention even withdrew their support for the Declaration to salvage their reputations.

Still, most remained firm. What’s more, their resistance achieved the effect they wanted – the backlash they received was so abusive and hyperbolic that the public sentiment began shifting toward the side of the Women’s rights movement.

The Expansion

The Movement’s start may have been tumultuous, but it was a success. The suffragettes began hosting new Women’s Rights Conventions every year after 1850. These conventions grew larger and larger, to the point that it was a common occurrence for people to be turned back due to a lack of physical space. Stanton, as well as many of her compatriots such as Lucy Stone, Matilda Joslyn Gage, Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, and others, became famous across the whole country.

Many went on to not only become famous activists and organizers but also to have successful careers as public speakers, authors, and lecturers. Some of the most well-known women’s rights activists of the time included:

- Lucy Stone – A prominent activist and the first woman from Massachusetts to earn a college degree in 1847.

- Matilda Joslyn Gage – Writer and activist, also campaigned for abolitionism, Native American rights, and more.

- Sojourner Truth – An American abolitionist and women’s right activist, Sojourner was born into slavery, escaped in 1826, and was the first black woman to win a child custody case against a white man in 1828.

- Susan B. Anthony – Born into a Quaker family, Anthony worked actively for women’s rights and against slavery. She was president of the National Woman Suffrage Association between 1892 and 1900, and her efforts were instrumental for the eventual passing of the 19th amendment in 1920.

With such women in its midst, the Movement spread like a wildfire through the 1850s and continued strong into the 60s. That’s when it hit its first major stumbling block.

The Civil War

The American Civil War took place between 1861 and 1865. This, of course, had nothing to do with the Women’s Rights Movement directly, but it did shift the bulk of the public’s attention away from the issue of women’s rights. This meant a major reduction of activity during the four years of the war as well as immediately after it.

The Women’s Right Movement wasn’t inactive during the war, nor was it indifferent to it. The vast majority of the suffragettes were also abolitionists and fought for civil rights broadly, and not just for women. Furthermore, the war pushed a lot of non-activist women into the forefront, as both nurses and workers while a lot of the men were on the front lines.

This ended up being indirectly beneficial for the Women’s Rights Movement as it showed a few things:

- The Movement wasn’t made up of a few fringe figures who were just looking to improve their own rights lifestyle – instead, it consisted of true activists for civil rights.

- Women, as a whole, weren’t just objects and property of their husbands but were an active and necessary part of the country, the economy, the political landscape, and even the war effort.

- As an active part of society, women needed to have their rights expanded just as was the case with the African American population.

The Movement’s activists began emphasizing that last point even more after 1868 when the 14th and 15thAmendments to the US Constitution were ratified. These amendments gave all constitutional rights and protections, as well as the right to vote to all men in America, regardless of their ethnicity or race.

This naturally was seen as a “loss” of sorts for the Movement, as it had been active for the past 20 years and none of its goals had been achieved. The suffragettes used the passing of the 14th and the 15th Amendments as a rallying cry, however – as a victory for civil rights that was to be the start of many others.

The Division

The Women’s Rights Movement picked up steam once again after the Civil War and many more conventions, activist events, and protests began to be organized. Nevertheless, the events in the 1860s had their drawbacks for the Movement as they led to some division within the organization.

Most notably, the Movement split into two directions:

- Those who went with the National Woman Suffrage Association founded by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and fought for a new universal suffrage amendment to the constitution.

- Those who thought that the suffrage movement was hampering the Black American enfranchisement movement and that women’s suffrage had to “wait its turn” so to speak.

The division between these two groups led to a couple of decades of strife, mixed messaging, and contested leadership. Things got further complicated by a number of southern white nationalist groups coming in support of the Women’s Rights Movement as they saw it as a way to boost the “white vote” against the now present voting block of African Americans.

Fortunately, all this turmoil was short-lived, at least in the grand scheme of things. Most of these divisions were patched up during the 1980s and a new National American Woman Suffrage Association was established with Elizabeth Cady Stanton as its first president.

With this reunification, however, the women’s rights activists adopted a new approach. They increasingly argued that women and men were the same and therefore deserve equal treatment but that they are different which is why women’s voices needed to be heard.

This dual approach proved to be effective in the upcoming decades as both positions were accepted as true:

- Women are “the same” as men in so far that we are all people and deserve equally humane treatment.

- Women are also different, and these differences need to be acknowledged as equally valuable to society.

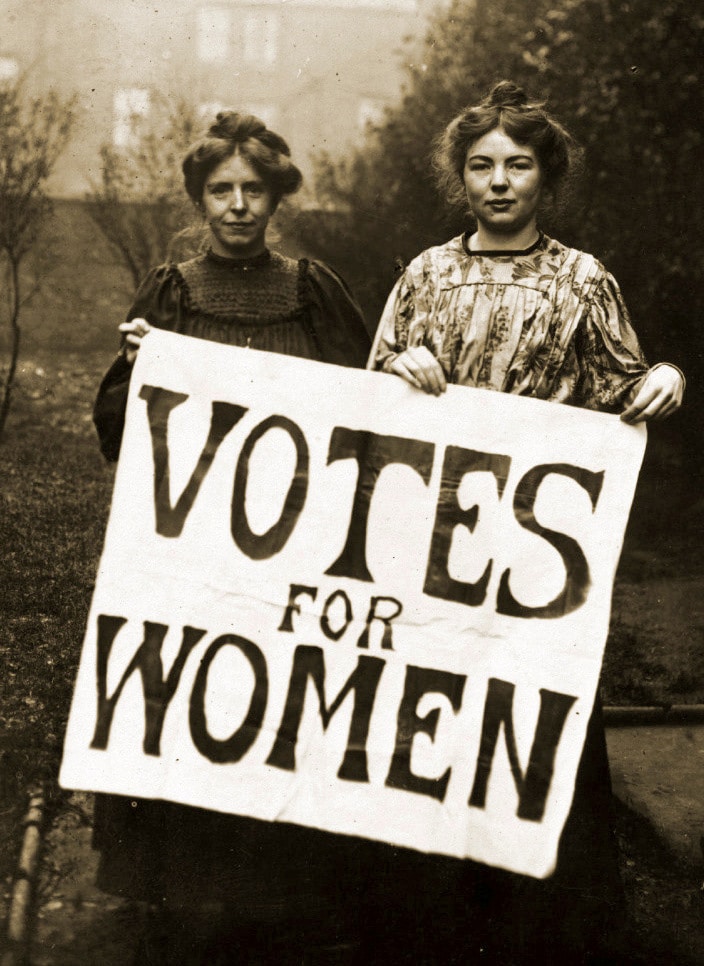

The Vote

In 1920, more than 70 years since the Women’s Rights Movement began and more than 50 years since the ratification of the 14th and 15th Amendments, the first major victory of the movement was finally achieved. The 19th Amendment to the US Constitution was ratified, giving American women of all ethnicities and races the right to vote.

Of course, the victory didn’t happen overnight. In reality, various states had begun adopting women’s suffrage legislation as early as 1912. On the other hand, many other states continued discriminating against female voters and especially women of color well into the 20th century. So, suffice it to say that the 1920 vote was far from the end of the fight for the Women’s Rights Movement.

Later in 1920, soon after the 19th Amendment vote, the Women’s Bureau of the Department of Labor was established. Its purpose was to collect information about women’s experiences in the workplace, the problems they experienced, and the changes the Movement needed to push for.

3 years later in 1923, the leader of the National Women’s Party Alice Paul drafted an Equal Rights Amendmentfor the United States Constitution. The purpose of it was clear – to further enshrine into law the equality of the sexes and to prohibit any discrimination on the basis of sex. Unfortunately, that proposed Amendment would need more than four decades to finally be introduced into Congress in the late 1960s.

The New Issue

While all of the above was going on, the Women’s Rights Movement realized that they needed to tackle an entirely different problem – one that even the Movement’s founders didn’t envision in the Declaration of Sentiments – that of bodily autonomy.

The reason why Elizabeth Cady Stanton and her suffragette compatriots hadn’t included the right of bodily autonomy in their list of resolutions was that abortion was legal in the US in 1848. In fact, it had been legal all throughout the country’s history. All that changed in 1880, however, when abortion became criminalized across the States.

So, the Women’s Rights Movement of the early 20th century found itself having to fight that battle as well. The fight was spearheaded by Margaret Sanger, a public health nurse who argued that the woman’s right to control her own body was an integral part of women’s emancipation.

The fight for women’s bodily autonomy lasted decades as well but fortunately not as long as the fight for their right to vote. In 1936, the Supreme Court declassified birth control information as obscene, in 1965 married couples across the country were allowed to legally obtain contraceptives, and in 1973 the Supreme Court passed Roe vs Wade and Doe vs Bolton, effectively decriminalizing abortion in the US.

The Second Wave

More than a century after the Seneca Falls Convention and with a few of the Movement’s goals achieved, the activism for women’s rights entered its second official phase. Often called Second Wave Feminism or the Second Wave of the Women’s Rights Movement, this switch happened in the 1960s.

What happened during that turbulent decade that was significant enough to merit a whole new designation for the Movement’s progress?

First, was the establishment of the Commission on the Status of Women by President Kennedy in 1963. He did so after pressure from Esther Peterson, the director of the Women’s Bureau of the Dept. of Labor. Kennedy placed Eleanor Roosevelt as the Commission’s chair. The purpose of the Commission was to document the discrimination against women in every area of American life and not just in the workplace. The research accumulated by the Commission as well as the State and local governments was that women continued to experience discrimination in virtually every walk of life.

Another landmark even in the sixties was the publishing of Betty Friedan’s book The Feminine Mystique in 1963. The book was pivotal. It had started out as a simple survey. Friedan conducted it on the 20th-year of her college reunion, documenting the limited lifestyle options as well as the overwhelming oppression experienced by middle-class women compared to their male counterparts. Becoming a major bestseller, the book inspired a whole new generation of activists.

A year later, Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act was passed. Its goal was to prohibit any employment discrimination on the basis of race, religion, national origin, or sex. Ironically, “discrimination against sex” was added to the bill at the last possible moment in an effort to kill it.

However, the bill passed and led to the establishment of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commissionwhich began investigating discrimination complaints. While the EEO Commission didn’t prove to be overly effective, it was soon followed by other organizations such as the 1966 National Organization for Women.

While all this was happening, thousands of women in workplaces and on college campuses took active roles not only in the fight for women’s rights but also in anti-war protests and broader civil rights protests. In essence, the 60s saw the Women’s Rights Movement rise above its 19th-century mandate and take on new challenges and roles in society.

New Issues and Fights

The following decades saw the Women’s Rights Movement both expand and refocus on myriad different issues pursued both on a larger and a smaller scale. Thousands of small groups of activists began working all throughout the US on grassroots projects in schools, workplaces, bookstores, newspapers, NGOs, and more.

Such projects included the creation of rape crisis hotlines, domestic violence awareness campaigns, battered women’s shelters, childcare centers, women’s health care clinics, birth control providers, abortion centers, family planning counseling centers, and more.

The work on the institutional levels didn’t stop either. In 1972, Title IX in the Education Codes made equal access to professional schools and higher education the law of the land. The bill outlawed the previously existing quotas limiting the number of women who could participate in these areas. The effect was immediate and staggeringly significant with the number of women engineers, architects, doctors, lawyers, academics, athletics, and professionals in other previously restricted fields skyrocketing.

Opponents of the Women’s Rights Movement would cite the fact that women’s participation in these fields continued to lag behind men. The goal of the Movement was never equal participation, however, but merely equal access, and that goal was achieved.

Another major issue the Women’s Rights Movement tackled in this period was the cultural aspect and public perception of the sexes. For example, in 1972, about 26% of people – men and women – still maintained that they would never vote for a woman president regardless of her political positions.

Less than a quarter of a century later, in 1996, that percentage had dropped to 5% for women and 8% for men. There is still some gap even today, decades later, but it does seem to be decreasing. Similar cultural changes and shifts occurred in other areas such as the workplace, business, and academic success.

The financial divide between the sexes also became a focus issue for the Movement in this period. Even with equal opportunity in higher education and workplaces, statistics showed that women were being underpaid compared to men for the same amount and type of work. The difference used to be in the high two digits for decades but has been reduced to just a few percentage points by the start of the 2020s, thanks to the tireless work of the Women’s Rights Movement.

The Modern Era

With many of the issues outlined in Stanton’s Declaration of Sentiments taken care of, the effects of the Women’s Rights Movement are undeniable. Voting rights, education and workplace access and equality, cultural shifts, reproductive rights, custody, and property rights, and many more issues have been solved either entirely or to a significant degree.

In fact, many opponents of the Movements such as Men’s Rights Activists (MRA) claim that “the pendulum has swung too far in the opposite direction”. To back this assertion, they often cite statistics such as women’s advantage in custody battles, men’s longer prison sentences for equal crimes, men’s higher suicide rates, and the widespread ignoring of issues such as male rape and abuse victims.

The Women’s Rights Movement and feminism more broadly have needed some time to readjust to such counterarguments. Many continue to position the Movement as the opposite of the MRA. On the other hand, an increasing number of activists are beginning to view feminism more holistically as an idealogy. According to them, it encompasses both the MRA and the WRM by viewing the problems of the two sexes as intertwined and intrinsically connected.

A similar shift or division is noticeable with the Movement’s view on LGBTQ issues and Trans rights in particular. The rapid acceptance of trans men and trans women in the 21st century has led to some divisions within the movement.

Some side with the so-called Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminist (TERF) side of the issue, maintaining that trans women are not to be included in the fight for women’s rights. Others are accepting the broad academic view that sex and gender are different and that trans women’s rights are a part of women’s rights.

Another point of division was pornography. Some activists, particularly of the older generations, view it as degrading and dangerous to women, while newer waves of the Movement view pornography as a question of free speech. According to the latter, both pornography and sex work, in general, should not only be legal but should be restructured so that women have more control over what and how they want to work in these fields.

Ultimately, however, while such divisions on specific issues exist in the modern era of the Women’s Rights Movement, they haven’t been detrimental to the Movement’s ongoing goals. So, even with the occasional setback here or there, the movement continues to push on toward many issues such as:

- Women’s reproductive rights, especially in light of the recent attacks against them in the early 2020s

- Surrogate motherhood rights

- The ongoing gender pay gap and discrimination in the workplace

- Sexual harassment

- Women’s role in religious worship and religious leadership

- Women’s enrollment in military academies and active combat

- Social Security benefits

- Motherhood and the workplace, and how the two should be reconciled

Wrapping Up

Even though there is still work to be done and a few divisions to be ironed out, at this point the tremendous effect of the Women’s Rights Movement is undeniable.

So, while we can fully expect the fight for many of these issues to continue for years and even decades, if the progress made so far is any indication, there are many more successes yet to come in the Movement’s future.